Remembrances—an installation by Gaither Stewart and Patrice Greanville

Like Yesterday

By Gaither Stewart

The 2006 version of Buenos Aires at the Café Biela shows no visible effects of the economic crisis the nation has only recently emerged from. Yet, underneath, the scars are there, not only from the economic crisis but especially from the moral crisis caused by the years of the dictatorship from 1976-1983. People of this rich barrio, like many Germans after WWII, are uncertain about what went wrong in a nation that permitted the horror of at least thirty thousand desaparecidos and the moral degeneration the terror engendered. As much as Beautiful Buenos Aires wants to come to terms with that past, it is still an elusive operation. Who is guilty is still an open question in Argentina. At least formally so since the social forces served by the brutal military dictatorship are clear.

One fourth of Argentina’s forty million people lives in Greater Buenos Aires, three million of them in the city itself. It is one of the major urban centers in the world. Buenos Aires is a concentrate of Argentina as Paris is of France. The problems of the nation are the problems of Buenos Aires. The problems of Buenos Aires are the problems of the nation.

EL CHOCLO (1)

The Music of Buenos Aires

My barrio here could be Paris or Madrid. It could be the Upper East Side in New York. White skins predominate. Though officially less than one per cent of Argentina’s population is of indigenous descent since the new Spanish arrivals simply “eliminated” the people they found here, and though a majority of people in north Buenos Aires are of European stock, the number of apparent mestizos even in chic Recoleta and Palermo continues to surprise me.

Yesterday I walked to the Retiro train station to take a look, for it is at train stations that one sees best the cross sections of a country. And they were there, in big numbers: the Indios and mestizos, the half-breeds and quarter-breeds. Maybe some are Bolivians or Indios from Brazil but most are Argentines.

In wandering around the huge city I find that an even greater number of persons have certain particular but elusive features—a square facial structure and thick cheekbones—in which I seem to see traces of man’s North Asian period that followed the diaspora of the first men from Africa, the original mother and motherland of all of us.

Although this is not the place for an anthropological survey, I am as usual on the qui vive for what links us all. I always hope to pinpoint the prototype of Man. I am continually searching for the Man in which I believe we all converge. On the plane from Rome to Buenos Aires, sitting among mainly Argentines, I saw in many faces what I thought was that original Man. Strangely and inexplicably those features were especially in the faces of white-skinned women. In these first days in Buenos Aires I have therefore intensified my search, convinced I will see the original Man here. I stop in crowds and peer into passing faces and sometimes I believe I see him.

There he is! There is Man!

The man from Siberia who never faltered, who never deviated from his southern course toward the bottom of the world, who filtered southwards down the still unnamed continent and became the “indigenous” Man, the first man in Argentina. Somehow he survived the Spanish invasion and the mass extermination. He both assimilated his Spanish executioner and was himself secretly assimilated. Again and again he mixed with the new blood arriving in waves from Europe, from Italy and Germany. Argentines marking the arrival of the Spanish five centuries ago on the Day with the ugly name of “Day of the Race” on October 12 wonder how best to call what happened here at the mouth of what they called the Rio de la Plata: Discovery? Meeting of cultures? Usurpation? Conquest?

They are right to wonder. None of the names apply.

Far too many people forget that Carlos Gardel was not only one of the best singers of all time, but also an extremely gifted and influential composer.

Por Una Cabeza (2)

(See full lyrics, translation and notes at the bottom of this article)

To backtrack a bit, I think of the early men from Africa who had first migrated to the northeast to Siberia, then across the straits to Alaska and then set out on their trek to the south. Some dropped out along the way. Some turned east to become the Cherokees and the Sioux. Others stopped in Mexico to become the Toltecs and the Olmecs. Others stopped in Peru and became the Incas. Finally Man arrived in Argentina, the end of the line. Until one day he, the survivor, met his lost brothers arriving from Europe. He met himself.

By then they had changed in appearance and in speech and did not recognize or understand each other. And they still do not know each other any more than they know themselves. Man is lonely in the universe. He is lonely without his long lost brother. He feels nostalgia and wonders who he is.

I stand outside the Retiro Station and watch my brothers pass. Try as I might I do not recognize them. Yet I know intellectually that we are both men from the same mysterious and disputed origins. We have been separated by the walls of history.

What is man, forever in search of himself and his lost brother, to think in the face of walls. Of the Berlin Wall? Of the wall surrounding the Jews in the Warsaw ghetto? Of Israel’s wall to keep out their Arab brothers? Of America’s construction of a thousand mile wall to separate itself from its brothers to the south? What are we to think of genocides of our brothers?

Gaither Stewart’s latest novel is The Fifth Sun (Punto Press). He serves as senior editor with The Greanville Post (TGP) and European correspondent for both TGP and Cyrano’s Journal Today. His home base is Rome.

Reminiscencias de mi Buenos Aires querido

(Or how I reached Buenos Aires via Naples)

Patrice Greanville

The soul of Buenos Aires is a soul filled with nostalgia. Great cities tend to be cold and businesslike, ruthless and impersonal in their dealings. New York comes immediately to mind in this regard; the summoning of its image when one speaks of a cold metropolis something of a cliché. Others, like Shanghai, we approach gingerly as one approaches a massive beehive where one’s humanity could swiftly vanish into a featureless common denominator. Buenos Aires is big, some porteños would proudly say huge. But there’s nothing impersonal about Buenos Aires. Buenos Aires often feels up close and personal, like a small town. Perhaps it is her Mediterranean fabric—half Spanish, half Italian, with generous sprinklings of other transplanted races, all embedded in the magnanimous embrace of the long-suffering, resigned, often despised Amerindian pachamama—that makes the character of this city so human, so captivating, so contradictory and so hard to resist. Buenos Aires is twice as big as Madrid, just about the size of London in population (the biggest metropolis in the EU), and ten times the size of Naples, but its aura of intimacy, the badly concealed mien of the old villorrio, its ability to tug at the heart is the same.

Like all big assemblages of humanity the Buenos Aires cultural DNA carries many infusions. The colonial Spanish pool, reinforced by 19th and 20th century migrations, remains strong, but the city can’t be properly recognized without acknowledging the enormous influence of Italians, chiefly from Sicily and the Campania. The Italians came and mostly remained in the River Plate estuary, rarely venturing beyond the city’s ample limits, the Argentinean hinterland, the realm of the cabecitas negras.

Most of them bore the scars of immemorial poverty, the erratic employment at home, a life of literal servitude made doubly awful by two global wars that shook the peninsula to its roots but did not remove the old social chains, disdain, and prejudices against mezzogiornini, and the lower orders, in general, an attitude that has not entirely died even in the 21st century. Out of this proud but dilapidated mix the Neapolitan strain soon became one of the most influential in the new land. Thus, in the City of Fair Ayre, more than any other ingredient, it was Naples that smoothed the excessive harshness and rigidity so typical of the Spanish character, a trick Neapolitans had mastered over centuries of close acquaintance with their onetime nominal Hispanic overlords.

Who are you, Naples? And how did you get to the banks of the River Plate?

Anyone who knows anything about these matters can attest that there’s no city in the world like Naples in terms of ostensible emotionality and popular talent for lyricism. Naples is the cradle of most famous Italian popular songs. O Sole Mio came from Naples. So did Torna a Surriento. And that enduring hymn to filial love, Mamma. There are many other songs like that: all beautiful, all sad (or poignantly joyous); all celebrating the most irrepressible emotions the human heart is heir to. All rendered in that curious hybrid vernacular that distinguishes the Amalfi region, a language that endlessly oscillates between Italian proper and old Spanish, never quite making up its mind.

Naples has a well deserved reputation for cunning resiliency, bordering on the bizarrely criminal. At times it can be downright comical. To many outsiders the inhabitants seem over-exuberant, histrionic, even caricaturesque. In his searing La Pelle (The Skin) native son Curzio Malaparte, himself a hybrid, an Italo-German with unsettled loyalties, painted Naples in the closing hours of WW2 as a sea of shifting humanity at wits’ end, future uncertain, with the streets and beds an arena of desperate Darwinism, the whole mess improbably supervised by a conquering, swaggering horde of supremely naive semi-barbaric Americans. The Germans were clearly foreign to the Neapolitan way, but the Americans were simply another species.

Against this backdrop Malaparte conjures up visions that could only make sense in a place as culturally supple and old as Naples, the site of a grand uninterrupted farandula. It could only happen in Naples, Malaparte assures us, because Naples is above all tolerant; like an old being it has seen it all, like an old mother, it forgives all. Genuine scandal cannot really faze her. The tumult that betrays internal emotions is alien to her character: too abrupt, too ill-mannered to be accepted into the wove of Naples instinctive gentility, every single one an expert in the art of savoir vivre. The external fireworks is another matter, for the sake of bella figura, an Italian imperative, but they too soon pass and calm is restored.

Indeed, only a culture as flexible and complicated as Naples can produce a femminiello, a testament to the people’s adaptability. As a Neapolitan scholar has pointed out, (3):

In the variegated world of homosexuality, still ill defined both scientifically and culturally, the position of the Neapolitan femminello is a privileged one…they live mostly in the poor quarters in a welcoming atmosphere, surrounded by good-natured consensus. They were born in a squalid slum, bereft of air and light, into families where promiscuity is the rule and all the children generally sleep in one bed…he is usually the youngest male child, ‘mother’s little darling,’ and tends to imitate his mother’s feminine sweetness…It is unusual for a poor family to view the femminiello as a family disgrace in any sense of the word; he is useful, he does chores, runs errands and watches the kids…and a mother would have no second thoughts about asking a femminiello to babysit.

This is what Malaparte well understood when he spoke provocatively in The Skin of the somewhat blatant “Congress of Homosexuals,” the “tide of Internationale of invertiti [those who are ‘inverted’] each one a ‘noble Narcissus,’ streaming back to Naples through broken German lines after the liberation of southern Italy in September 1943—back to Naples, the capital of the ancient Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and the most important carrefour of the forbidden vice. They brought with them the hope that the “liberation” of Europe from tyranny would somehow at last translate into lasting sexual freedom.* (4)

Against such visions, the legend that Neapolitans managed to steal a whole American destroyer, without leaving a trace (not to mention untold numbers of lesser objects), seems tame. Anything to survive, because life, after all, is the ultimate accomplishment.

In her award-winning film Settebellezze Director Lina Wertmuller paid mordant tribute to the supreme Neapolitan “survivor”, depicting him as a mass of contradictions in which opportunism, sentiment, and honor are in constant combat with none winning the decisive upper hand. The quest for dignified opportunism—”onore“— is scarcely unique to Naples. Other regions of Italy, notably Sicily, also rate as powerful entrants in the contest, and to some extent the rest of the world, for the art of survival against great odds is almost a universal gift, often acquired out of necessity. That said, what distinguishes Naples is that, hard as she may need to be, she’s never afraid to show her soft side, her maternal side, and her wiles are always displayed with memorable haunting panache. Vittorio de Sica, the man who gave us Ladri di Biciclette and other masterpieces, described Rome as the calculating mind of Italy, but Naples, he averred, was her heart. Who could have thought that the same heart would find some day a new home 7,000 long miles from the lap of the Vesuvius in the Southern Cone of Latin America?

Gardel’s debt to Naples

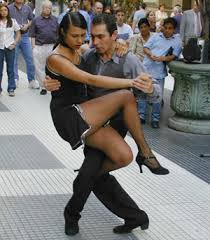

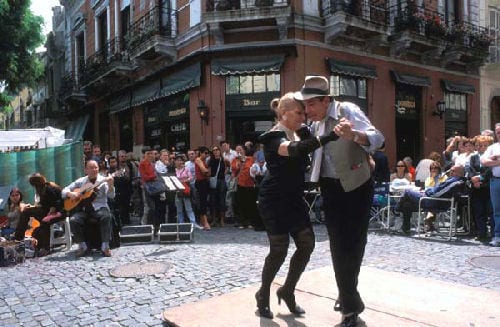

The music of a culture reflects its temperament, and the music of the people of Buenos Aires is the tango. The tango speaks to losses, just like Naples’ songs. The poor feel its message deeply. Unfinished journeys. Defeats. Prolonged absences. Fidelity to one’s great primal loves. The inexorable passage of time. Its music has echoes of classic Eurolatin melodiousness with the cadence of the new Amerindian rhythm. The passion that infuses its steps has roots firmly planted in both continents.

The tango’s pre-eminent artist, never surpassed, is Carlos Gardel, at once a versatile, unique, deeply haunting interpreter and gifted composer of scores of songs, many arranged with the aid of his loyal friend in life and death (literally) the lyricist Alfredo Le Pera.(2)

Gardel was one of the first truly international superstars. His fame reached not only every corner of Latin America, but Paris, (where he was revered), Berlin, London, Tokyo, Helsinki, and even Russia. Equally surprising, he was known even in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles (America is usually a planet apart)—where he went to make some recordings and movies for the internal regional Latin markets. Despite the brevity of his visits he impressed many local artists, including a callow Frank Sinatra, whom he counseled to get serious about his crooning.

Gardel was not Neapolitan. Of very humble origins, he was born in Toulouse, Southern France, in 1890. His mother, apparently a laundress, left the city a few years later, probably to escape the stigma of having a child born out of wedlock. In early 1893 in Bordeaux, France, mother and son boarded the ship SS Don Pedro and sailed to Buenos Aires, arriving on 11 March 1893. Gardel grew up watching his mother battle poverty, but the wounds of that squalid life were quickly palliated by the boy’s quick ascent from anonymity and the almost tribal, fierce love he received from everyone in the barrio, la barra de los muchachos.

In many regards, buoyed by the support of his friends, many immigrant sons and daughters themselves, el francesito—”frenchie”—as his friends called him, managed to escape the more sordid and depressing injuries of class. Gardel never forgot his roots nor that early embrace, and his love for the common people soon found expression in multiple motifs that seem now, in retrospect, like the artist’s unconscious effort to repay a big emotional debt.

Both Buenos Aires and Naples are unapologetically sentimental and much of Gardel’s music, like tangoes in general, is sentimental. But this is not cheap sentimentality; classic tango has nothing mawkish in it, nothing soap operatic. Tango—like Jazz— is not self-pitying, though its natural call is to witness the loser’s progress, with whom it identifies, a path full of frustrations, love’s disappointments and bittersweet illusions. Tango sings the blues in Spanish.

Journeys are particularly important to the tango repertory and Gardel often incorporated the idea in his best compositions. The hard transplantation to a new continent resonated with a collectivity full of immigrants, economic exiles, in reality, and tango spoke to their repressed pain. Those that have never uprooted themselves from native soil, or been forced by circumstance into foreign exile will have trouble understanding. Such journeys are both geographic and emotional, and then there’s the journey of life itself, the one in which our memories constitute the main road.

.

The compulsion to return—”Volver”

Gardel was quick to seize on that motif. He felt it intensely. For Gardel life was a round trip: No matter where we begin, we always long to go back to our point of origin, to the land, to the spot that saw us in our youth, to sort things out a final time. The heart demands it. Not for nothing the old Latin word for “remember” is “recordare”. Fellini’s homage to his youth was called Amarcord—I remember. For recordare is not to pass a thought through the mind but through the heart. Il cuore. We remember with the heart. The mind just organizes our words; the heart controls the tears, the logical punctuation for the inexpressible inside.

I have mentioned Naples and now Gardel at some length because without knowing something about them it’s really impossible to comprehend Buenos Aires. Naples in her songs sheds tears for those who have left in search of new horizons and for those left behind, counting the days when a longed-for reunion will be possible. The journey home is both geographic and biographic. The miles and the years that separate one from one’s point of departure, the moment when the first emotional debts are incurred, resonate with the soul of the old porteño. They understand what that implies. And Gardel is always there to show them the way. In Volver, one of his signature pieces (lyrics by his collaborator Alfredo Le Pera) Gardel paid homage to many of the motifs spelled out earlier, and that remain dear to the soul of Buenos Aires: the voyage of life, the return to settle one’s emotional accounts, the brevity of our existence, the persistence of orphaned illusions from youth. As Le Pera wrote,

To feel

that life is a mere breath

that twenty years is nothing…

Tango is for adults. Those who have never grown up, who never lived, who are yet to be hit by life, cannot grasp what this type of music says. And that’s too damn bad.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Patrice Greanville is The Greanville Post‘s founding editor. He misses Buenos Aires a great deal, because while the great city may have plenty of commerce and business, she’s not about business.

Volver (Carlos Gardel)

(Lyrics and commentary in appendix below.)

Appendix

In the songs that follow I provide a brief commentary on the cultural motifs discussed above, especially the leave-takings and returns. The duty to the mother (as felt and understood primarily by commoners or the poor, since the rich have always marched to a different, largely unsentimental tune); the debt to the old paese, and the trip back to the places that witnessed our youth. In some cases a translated excerpt suffices to convey the force and purity of these enduring compositions. A video version accompanies each selection. Complete lyrics for all these songs can be easily found through a simple Google search.

MAMMA (Cesare Andrea Bixio; lyrics by Bixio Cherubini)

Mamma, son tanto felice

Perche ritorno da te

La mia canzone ti dice

Ch’ il pi bel sogno per me

Mamma son tanto felice

Viver lontano perche

Mamma I am so happy

Because I’m returning to your side

My song tells you

That this is the most beautiful dream for me

Mamma I am so happy

To live far away—whatever for?

Mamma, solo per te la mia canzone vola

Mamma, sarai con me, tu non sarai piu’ sola…

Mamma, only for you my song takes flight

Mamma, you will now be with me, you will no longer be alone.

•••

Tu non sarai piu’ sola…

For me, the real thrust to the heart comes with this simple line. You will no longer be alone. How many sons have abandoned their mothers for personal reasons unaware of the pain they caused? You are life…and for life I swear, I will never leave you again.

Mamma (Luciano Pavarotti)

Vide’o mare quant’è bello,

spira tantu sentimento,

Comme tu a chi tiene a’ mente,

Ca scetato ‘o faie sunnà.

Look at the sea, how beautiful it is,

it inspires so many emotions,

like you do with the people you have at heart.

You make them dream while they are still awake.

Guarda gua’ chistu ciardino;

Siente, siente sciure arance:

Nu profumo accussi fino

Dinto ‘o core se ne va…

Look at this garden

and the scent of these oranges,

such a fine perfume,

it goes straight into your heart,

E tu dice: “I’ parto, addio!”

T’alluntane da stu core…

Da sta terra de l’ammore…

Tiene ‘o core ‘e nun turnà?

And you say: “I am leaving, goodbye.”

You go away from my heart,

away from this land of love,

And you have the heart not to come back.

O SOLE MIO (Eduardo di Capua; Lyrics by Giovanni Capurro, 1898)

O Sole Mio Di Capua

VOLVER (To Return, Music by Carlos Gardel; lyrics by Alfredo Le Pera)

Yo adivino el parpadeo

de las luces que a lo lejos

van marcando mi retorno.

I discern the faint blinking of the lights

that far away

are marking my return

Son las mismas que alumbraron

con sus pálidos reflejos

hondas horas de dolor.

They are the same that illuminated

with their pale reflections

terrible hours of heartache

Y aunque no quise el regreso

siempre se vuelve

al primer amor.

And although I did not want to return

You always go back

to your first love

La vieja calle

donde me cobijo

tuya es su vida

tuyo es su querer.

The old street

that harbors me now

life and love

belong to you

Bajo el burlón

mirar de las estrellas

que con indiferencia

hoy me ven volver.

Under the mischievous

gaze of the stars

that now with some indifference

watch me come back.

Volver

con la frente marchita

las nieves del tiempo

platearon mi sien.

To return

withered forehead

the snows of time

have silvered my temples.

Sentir

que es un soplo la vida

que veinte años no es nada

que febril la mirada

errante en las sombras

te busca y te nombra.

To feel

that life is a mere breath

that twenty years is nothing

how feverish my eyes

stumbling in the shadows

seek you out and call your name.

Vivir

con el alma aferrada

a un dulce recuerdo

que lloro otra vez.

To live

with the soul clinging

to a sweet memory

that I mourn once again.

Tengo miedo del encuentro

con el pasado que vuelve

a enfrentarse con mi vida.

I fear the encounter

with the past that will

confront my life.

Tengo miedo de las noches

que pobladas de recuerdos

encadenen mi soñar.

I fear the nights

that populated with memories

will now enslave my dreams.

Pero el viajero que huye

tarde o temprano

detiene su andar.

But the traveler that flees

sooner or later must come

to a halt.

Y aunque el olvido

que todo destruye

haya matado mi vieja ilusión,

And although oblivion

that destroys everything

may have killed my old illusion,

guardo escondida

una esperanza humilde

que es toda la fortuna

de mi corazón.

I keep hidden

a humble hope

that constitutes the

entire fortune of my heart.

(Bis)

Volver

con la frente marchita

las nieves del tiempo

platearon mi sien.

Sentir

que es un soplo la vida

que veinte años no es nada

que febril la mirada

errante en las sombras

te busca y te nombra.

Vivir

con el alma aferrada

a un dulce recuerdo

que lloro otra vez.

To live

with the soul clinging

to a sweet memory

that I mourn once again.

(1) “El Choclo” (Spanish: meaning “The Corn Cob”) is a popular song written by Ángel Villoldo, an Argentine musician. Allegedly written in honour of and taking its title from the nickname of the proprietor of a nightclub, who was known as “El Choclo”. It is one of the most popular tangos in Argentina. The piece was premiered in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1903 – the date appears on a program of the venue – at the elegant restaurant El Americano on Cangallo 966 (today Teniente General Perón 966) by the orchestra led by José Luis Roncallo.

Interpreted by Katica Illényi and her sister. Katica Illényi is a Hungarian violinist and singer. On her concerts she plays classical pieces on the violin, jazz standards, world famous movie soundtracks and evergreens. She was born in Budapest, Hungary, and comes from a classical music family. [Violin: Katica Illenyi (Illényi Katica); Cello: Aniko Illenyi (Illényi Anikó); Angel G. Villoldo: El Choclo, tango]

This string quartet version of the beloved tango, featured in the Al Pacino movie “Scent of a Woman”, was played by Dominika Dancewicz, Johnny Chang, Violins, Hillary Schoap, Viola and Olive Chen, Cello. The concert was held at Jennyoga in Houston, TX. Audio/Video productions by Mark Chen Photography.(2) Le Pera died with Gardel in June 1935 in a plane crash in Medellín, Colombia. Gardel was only 44.

| In this epic tango, composed by Carlos Gardel, the interplay between losing at the race track and losing with women is carefully woven into a poem to fate. |

Version en castellano | English version (P. Greanville) |

| Por una cabeza de un noble potrillo que justo en la raya afloja al llegar y que al regresar parece decir: no olvides, hermano, vos sabes, no hay que jugar… Por una cabeza, metejon de un dia, de aquella coqueta y risueña mujer que al jurar sonriendo, el amor que esta mintiendo quema en una hoguera todo mi querer. Por una cabeza todas las locuras su boca que besa borra la tristeza, calma la amargura. Por una cabeza si ella me olvida que importa perderme, mil veces la vida para que vivir… Cuantos desengaños, por una cabeza, yo jure mil veces no vuelvo a insistir pero si un mirar me hiere al pasar, su boca de fuego, otra vez, quiero besar. Basta de carreras, se acabo la timba, un final reñido yo no vuelvo a ver, pero si algun pingo llega a ser fija el domingo, yo me juego entero, que le voy a hacer. | Losing by a head of a noble horse who slackens just down the stretch and which when it comes back it seems to say: don’t forget brother, You know, you shouldn’t bet. Losing by a head, a passionate tumble with that flirtatious and cheerful woman who, swearing with a smile a love she’s lying about, burns in a blaze all my love. Losing by a head all the craziness; her mouth that kisses wipes out the sadness, and soothes the bitterness. Losing by a head if she forgets me, who cares if I’m lost my life a thousand times; what is there to live for? Many deceptions, losing by a head… I swore a thousand times not to try again but if a look wounds me on passing by her lips of fire, I want to kiss them again. Enough of race tracks, no more gambling, a photo-finish I’m not likely to see again, but if a pony looks like a sure thing on Sunday, I’ll bet everything again, it can’t be helped! |

(4) Jeff Mathews, The Femminiello in Neapolitan Culture.Below, on the next page, how North Americans see the tango, and execute it, literally, for good and for ill.

Awesome post.