Interview with Gaither Stewart about his Novel: The Fifth Sun

By JP Miller

JPM: The Fifth Sun seems to be a literary departure for you. It is a very modern novel but at the same time there is something timeless about it. The action begins in Rome and moves to New York and Mexico City. After your work on the Europe trilogy, you have again gone back to America and its dichotomies. Did you have some unfinished business with your past that informed this new novel?

GS: I think that is partially right. I left Europe for Mexico in 1996 where I intended completing this novel which I’d begun in Rome. After 18 months in Mexico, my Italian wife and I decided to go to New York, where we had a small apartment and where we stayed for over two years. I claimed my intention was to “rediscover America” after many decades of absence. However, since most of our friends there were Italians I’d known in Italy and Russians I’d met in Rome after their exit from the USSR in the 1970s, I hardly met any real Americans or even spoke much English. When my wife threatened divorce if we didn’t return “home”, we went back to Rome without my rediscovering America … though I had completed much of the novel and written many short stories set in Mexico.

As a setting for the book, you talk about the Mesoamerican conception of The Fifth Sun as the final period of time after the four previous epochs have passed. Is this some kind of warning to the reader and the characters of the book? Does this aspect of accelerating time drive them to their outcomes?

I don’t believe I had that thought in mind, but for people who constantly live with the idea that time can end at any moment, time must accelerate considerably. My characters were driven by their urge to realize themselves in one way or another and they agreed that ancient Mexico offered the place to accomplish this.

One political notion you entertain in The Fifth Sun is that of the huge divide between the ancient culture of Mexico and the newly formed USA. You refer to the Rio Grande as a division of not only space but also time. What does the book tell us about this division? And can you see a time in the future when the Indio cultures revive and the ancient practices are resurrected?

Well, driving across the Rio Grande in Laredo, Texas is an astounding experience. The moment your front wheels touch the Mexican side of the bridge, you feel you are in another world. Soon you wonder if you have moved back in time or if you are perhaps zipping ahead into an unknown future. You might recall the old Mexican saying, “Pobre Mexico, tan lejos de Dios y tan cerca de Los Estados Unidos.” Poor Mexico, so far from God and so near The United States. Or you might think of the high “Wall of the Gringos” that the USA is completing to separate even more the two coutries sharing the same continent. Strange impressions! Many of the ancient practices of the indigenous peoples there are still alive and somehow integrated into Mexico’s Catholicism imposed by the Spanish conquistadores. I note in the foreword to this novel that “The Spanish liquidated the indigenous elite, but not the masses who in Spanish eyes were ‘saved’ by baptism.” Concerning the preservation of practices of the indigenous peoples, an Cora mystic once told me to remember that Mesoamerica has seen two millennia of civilizations that are not Western. There are remains from the year 200 of Teotihuacan, the first great city of the Americas. In every Mexican, he said, those pasts are present. Today, although the language and religion and political and cultural institutions of Mexico are Western, perhaps also because of the separation of the USA from Mexico, the watershed of Mexico seems to slope in another direction—toward that of its Indio past.”

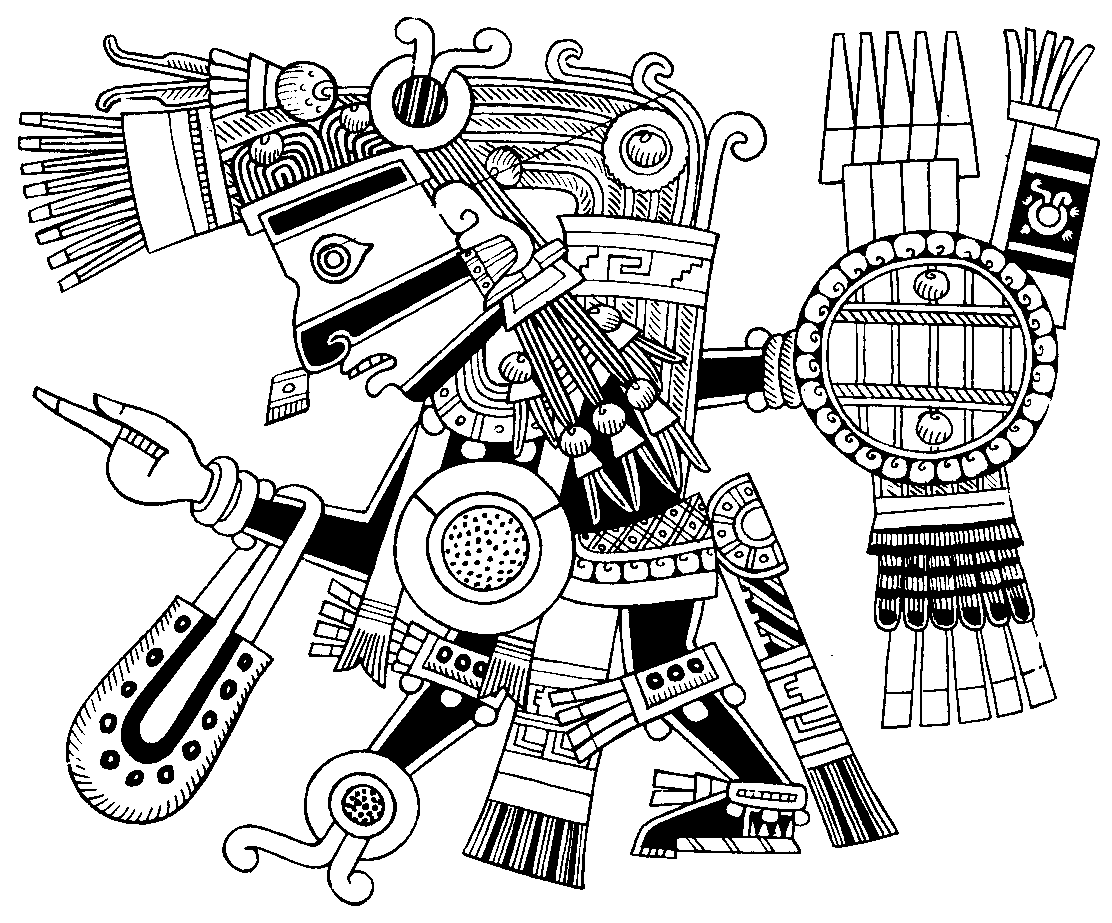

Your depictions of gruesome ancient Aztec religious practices and the highly ritualized, often torturous, and suspect practices of the modern Catholic Church often parallel to one another in The Fifth Sun. Are you trying to tell the reader that there is no real difference between the two religious practices? Do we repeat the same myths, sacrifices, and delusions?

History shows that Catholicism was no slouch when it came to torture. The Spanish Inquisition, for example, showed its mettle against so-called heretics, as did the Roman Church against the Cathars holed up in southern France. I don’t believe the Catholic Church had any ideas of saving the world as the Aztecs did, but of enforcing orthodoxy as they interpreted it and of course securing their own positions. To claim that such Aztec and Catholic rituals are often parallel would not be stretching historical realities. The Aztec ritual of human sacrifice was indeed gruesome, no matter whether the number of victims was in the hundreds, thousands or millions. Likewise, the estimates of the number of heretics executed by the Catholic Church, most frequently first tortured and then burned at the stake—practices most certainly more horrible than the Aztec ritual on the killing stones of their pyramids—vary from hundreds to thousands and even millions. Aztec human sacrifices were made to placate the gods and save the fifth world in which we still live. Catholic torture and burning alive was carried out in the name of purity of faith which damaged the image not only of the Catholic Church but of organized religions in general.

From time to time the modern Church itself tries to come to terms with that past. Late last century Pope John Paul II uttered the famous words in this regard: “Forgive us, Lord. Never ever again.” The ritual of human sacrifice has been, as you say, repeated in many organized religions: Judaism sacrificed animals to placate their god, but according to Genesis, God called on Abraham to sacrifice his own son Isaac in order to test his loyalty, only to spare his life at the last moment, perhaps suggesting that the practice of human sacrifice was a possibility/probability.

I must have had in mind the idea of human sacrifice on the altar when I wrote the opening scene of The Fifth Sun in which I show the ceremony of the confirmation of the seminarian, Diego, spread-eagled on the marble floor of St. Peter’s in Rome. Yet reality shows us that such religious rituals and rites are as a rule deleterious despite, or perhaps because of, the intended test of “loyalty” or “faith”. I find it curious that politics and ideology likewise depend on rites and ritual to “bind” followers, calling to mind “the binding” of Isaac to the altar as an act of faith. Symbols, rites and rituals are of course powerful ideological phenomena that express political statements about oneself and the world as in Mexico’s indigenous Cora and Huichol peoples in the novel.

One of the themes that run through many of your books is displacement. In The Fifth Sun that theme is continued. The characters of Diego and Sarah both seem to be uprooted and distant from their beginnings or, perhaps, rather their natural place in the world. They are expatriates. Your own life is a story of moving from one place or tradition to another and looking back to write about it. You are an expatriate. Was it easier to write The Fifth Sun, and about past locales, at a distance?

Yes, displacement is a major theme in most of my work. Every character is uprooted. Uprootedness and situatedness concern most everybody and I have never decided that one is better than the other. I have moved around quite a bit but not as much as it might seem–in my case different countries rather than different states.

You use the word expatriate, which is not one of my favorites.

The word exists in my vocabulary chiefly in a negative sense. Somehow it smacks of specious romanticism. Uprooted from one’s origins, OK. I think it must be the bad taste the word ‘expat’ has left in my mouth from the time Americans arrived in, say, Paris, after WWI and hung around for some years because a dollar went a lot farther in Paris than in New York. But 99.9% of those expats in the end went back where they came from. This is not to say that most foreigners living in a different society than the one in which they grew up don’t remain foreigners. They do to a great extent. I don’t consider Diego and Sarah or the other uprooted characters in this novel as expatriates.

In general, I prefer to get down the story line and define the characters in my mind at least before leaving a place where my story is set. I wrote a lot of ASHEVILLE there but finished it in Rome … and the same for THE FIFTH SUN.

What is it about displacement that informs your work so well? Like Sarah and Diego, do you always yearn to be somewhere else? Like them, do you yearn to belong?

Oh, yes, precisely. I love the places I have been. I have never seen a place — well, hardly — that I didn’t wonder how it would be to live there, and I continue to miss the best places I’ve known. As a rule I try to acclimatise myself as quickly as possible, learn as much of the language and culture as I can and then act as if I’d lived there forever. I want to belong, but in my heart I realize I do not.

While I have covered some similarities or recurrent themes in this interview, The Fifth Sun is different from your overtly politically themed and didactic books. Is this an indication of what we are to expect in the future? Have you mellowed? Have you gone back to Asheville?

I don’t believe that is the case … that I have mellowed I mean. Most of my work has a political base because that is the way I think. And you are right; I do write didactic books. I suppose most novels are didactic in one way or another. They must be. Most certainly, the writer wants to remake the world. He wants to be useful. I personally want to see the heroic in a fictional hero. I don’t want lies but counsel on how to live better. On the other hand, to describe poor people as happy simply because they finally have shoes is nonsensical and the portrayal of the masses as happy because a new political party is in power is deceit. In the same fashion, I find the depiction of globalization as the spread of democracy, security, and well-being not only absurd, but immoral and evil. War is not peace. Disasters will always be disasters. And it is insane to call catastrophes victories for mankind.

It’s a question of balance between reality and fantasy in fiction. Some of my books, such as my Europe Trilogy consisting of the already published novels, The Trojan Spy and Lily Pad Roll, and Time of Exile yet to appear, are more heavily politically weighted. Yet Asheville, in which I had the idea of an attempt at coming to terms with the city where I grew up, also carries a greater political message than might seem apparent. For example, though that novel is more symbolic and personal at the same time, I also show the strategy of tension at work, the method by which political power uses fear to justify special laws of suppression and police oppression, and to keep people cowed and in line. The same in The Fifth Sun in which the former priest Diego finds his true calling and fulfillment in the worst shantytown of Mexico City which with his help becomes a lighthouse for the poorest of the indigenous peoples of the country. And not to be forgotten, both Michele and Sarah are communists.

Your character, Sarah, is a tragic figure and seems to represent the lost, new character of the US, looking for definition. Like Sarah, is the US a tragic character in the political and social world around us?

It’s an interesting question. Sarah most certainly is a tragic figure (only by chance is she of American nationality). Abandoned by her father, but rich and spoiled, she is searching for something to believe in. She passes through various religions and people as well and she wants both her companion Michele and unobtainable Diego, but she finds only madness. So anyone who desires can trace out parallels with a tragic and lost America, alone in the world with only their Americanism and Exceptionalism to hang onto—whose people, however, are not even aware of the tragedy at work as Sarah is.

Your four main characters, Sarah, Diego, Michele and Robert Jay approach life from very different vantage points. But they seem to desire similar things, or rather desire hope itself, and at the same time desire to escape an ordinary life. Sarah notes that she would like to be possessed. Does Sarah simply search out love or does she want something more tangible to hold onto? Does she want to escape insanity or embrace it?

Most definitely, you hit the nail on the head: after finding no satisfaction in the many directions she has tried, she wants to embrace her insanity and hold it as her own.

Although Diego stumbles along with faithless feelings, homosexual longings, and abandons the church, does he, ultimately, want faith, or a simple physical connection?

Of course he yearns for the physical connection and the human love that he finds, but the other side of him wants to escape the Catholic Church and to truly do the world some good. He has to leave the Church in order to become a believer and a whole, independent person. I found it interesting that the new Pope of the Roman Catholic Church, Francesco, recently said that one can lead a Christian life without being as believer.

The other characters like Michele, Robert Jay and Diego are often caretakers of Sarah. Does this chore leave them out of any personal epiphany such as Sarah seems to experience in Mexico? Or does Sarah finally find only her madness?

They each take care of Sarah, apparently the weakest of the four. Yet each of them encounters a certain epiphany: Michele as an aid to Diego in the Mexico City shantytown waiting for Sarah’s return; Diego in his dedication to the poor who still call him “Father” even though he has left the Church; and Robert Jay who finds love and a real cause to live for in his economic support of Diego’s crusade for the poor. And Sarah? Well, in her case we have to accept that she embraced her insanity as the most lucid act of her life.

Diego’s sexuality is confused by preference at times but clear in its intentions of release. Should Diego get condemnation, solace, or indifference for his sexual unions with young men? Is this a condemnation of the Catholic Church and its decadence?

Diego in my mind is a living condemnation of the official Catholic Church. And he merits our greatest love and support for his ultimate rejection of that Church and his personal dedication to the poor, becoming a lighthouse for the poorest of the indigenous peoples of the country.

The alienation from life that your characters struggle with is a very strong statement and a continuation of postwar philosophy and literature. Did you consciously provide this existential conundrum for the reader? Is the disappearance of Sarah an analogy for the disappearance of all of us?

You’re right to note the theme of alienation in my work, a theme reflected in the displacement we spoke of earlier. But I had no special analogies in mind with the disappearance of Sarah. And disappearance is the proper word, for we don’t know if she finds something, anything at all, in the jungle or if her search simply ends there.

Is the ceremony in Mexico where Sarah eats peyote a psychedelic experience that releases her madness? Or is what she experiences a revelation for her understanding of the ancient gods? Or both?

I had in mind Sarah the person who had to investigate and taste all of life’s possibilities. Sarah, who speaks of “magic Mexico” and the triangle of bluish-black mountains filling the triangular plateau of Mesoamerica forming a gigantic pyramid surrounded by seas as “the top of the world”. Before going to the Indio festival she discussed the effects of peyote on a whole people of the Cora town, which at times seemed to interest her more than the possible effects on herself. Maybe that experience did in fact release her madness. For she was never the same afterwards. That was Sarah!

Finally, The Fifth Sun is truly a more commercial, mainstream work when compared with some previous novels. Was that your intention from the beginning?

Not at all. Since this was my first attempt at a wide-ranging novel in places I knew rather well and with a canvas of complex characters, I simply wanted to write a good book.

_________________________________

JP Miller, who interviewed Gaither Stewart, is an author and journalist. Among his work is Born to Run which appears in the Southern Cross Review and The Deep Blue Goodbye which was published by The Literary Yard. His journalistic work appears in Potent Magazine. He lives in Manteo, North Carolina, beside the Atlantic Ocean.

Editor’s Note: The Fifth Sun is currently scheduled for publication by Punto Press this fall.