=By= Gaither Stewart

The worldwide influence of the Roman Catholic Church emanates from the Holy See,which is the Church’s central government headed by the Pope and physically located within the territory of the Vatican State inside the city of Rome with a population of 821. The Holy See has diplomatic relations with world nations which maintain two separate embassies in Rome: one to Italy and one to the Holy See. Now why the hell, one wonders, should Argentina or the USA, China or Gabon maintain diplomatic relations with a church? Likewise the Holy See has its embassies around the world, the nunciatures, while from day to day the Roman Church insists on meddling in Italy’s and world affairs. Today the Roman Catholic is effectively blocking new legislationon on same sex marriages and concommitant rights in Italy and other countries. One of the first demonstrative acts of each new pope is a triumphant cortege through the streets of “Italy”, just across the Tiber River from the Vatican.

One Sunday morning in the residential wasteland of Queens, New York, a friend I only thought I knew cited a famous quote of T.S. Eliot, words, my friend said, that had changed his life. As we lumbered through the barren streets of a non-descript neighborhood of non-descript houses and miniscule front yards of dry yellow grass, he suddenly took my arm and apropos of nothing pronounced:

“The last temptation is the greatest treason:

To do the right deed for the wrong reason.”

To the two young men walking through dismal Queens, both inebriated with the hubris of youth and morning vodka, two doubters unmindful of even the possibility of God and the debate raging about it, those words spoken in the suburban desert rang humbling, menacing and earth-shaking. Silence followed. Neither of us commented.

In the many years since that day in Queens I have never seen the Eliot play performed, and of the film of the same name I recall chiefly the scenes of debauchery of two young friends of 12th century England, one a King, the other his Chancellor and future Archbishop of Canterbury.. Still, the text of Murder in the Cathedral is enduring and lives apart from the performance of play or film as befits the artistic work of a Nobel writer (1948).

At home in Rome I occasionally I pull down from the shelf the azure and deep red Faber & Faber edition of the book, anxiously awaiting the lines I first heard on that hot Queens street. Now, in these spring-like winter days I by chance saw a documentary film on the murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket and as a Rome resident I follow Pope Francis’ bid for more temporal power, often with the 12th century Archbishop, Thomas Becket, in mind.

Living in Catholic Rome and in the proximity of the Islamic world makes you constantly aware of the age-old persisting power struggle between state and church. The Roman Catholic Church seems to see temporal power as the chief aim of its ministry on earth while an analogous dichotomy between state and religion exists on the Islamic side of the Mediterranean Sea.

In any case, I find that Eliot’s play is an auspicious start for a look at the classical power struggle. The individual’s opposition to authority as was that of Thomas Becket, is even more pertinent in today’s globalization than it was in Eliot’s time in the 1930s when fascism was rising in Europe. Although Thomas Becket’s internal struggles are the essence of the play, the of secular vs. religious power continues to plague mankind. Those two struggles are the subject of this essay.

PART ONE

The Events

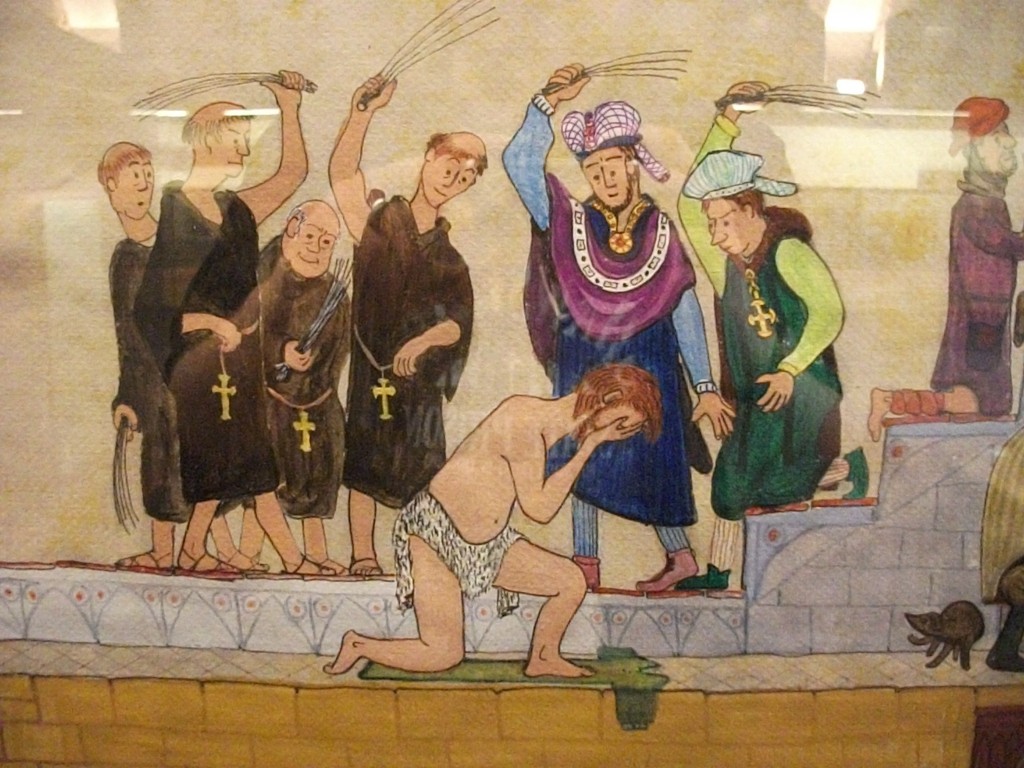

In 1163, the two friends, Thomas Becket (1118-1170), Archbishop of Canterbury and the English King, Henry II (1133-1189), quarreled over the respective power roles of the English Church and Henry’s state in change. So stormy did the dispute become that Becket escaped to France to rally support for the Church against the pressures of the State of Henry II. Seven years later, after an apparent reconciliation with his old friend, Becket returned to England only to be murdered in his Canterbury cathedral by four of Henry’s knights.

CC BY by Ben Sutherland

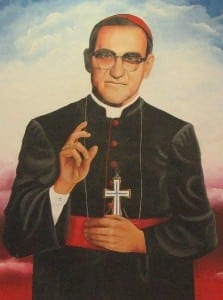

As Thomas had intimated 800 years earlier, Romero said: “If they kill me, I shall arise in the Salvadoran people. If the threats come to be fulfilled, from this moment I offer my blood to God for the redemption and resurrection of El Salvador. Let my blood be a seed of freedom.”. Though he is already called San Romero in El Salvador, a saint-martyr for the faith, the Roman Church still rejects his sanctification because it would be the same as approving the radical pro-poor movement, Liberation Theology, which during the Cold War (and still today) was seen by political power as a Marxist Trojan horse that would allow communism into South America. The complex procedure for Romero’s canonization only began in 1997, twenty years after his murder. Still not a Church saint, Romero was merely beatified as a sop to the “people” by Pope Francis on May 23, 2015.

In the England of Henry II, the Crown and the Church were at war for supremacy. Thomas Becket was weaker and had to die. His was a martyr’s death. Three years later he was canonized and pilgrims flocked to his tomb, including a repentant Henry II himself, in search of epiphany.

Mural of Oscar Romero as a Monseñor by Giobanny Ascencio y Raul Lemus- Grupo. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The reality was less a story of martyrdom of Becket than it was a story of a political assassination, relevant in all times. While Romero’s assassination was in the name of capitalist imperialism, Thomas was murdered by the State of King Henry II in order to supplant Church law with the King’s State courts, to introduce trial by jury and constitutional and legal reforms. His assassination was a case of the wrong thing though for the right reason.

Eliot’s play is thus not just about the murder of Thomas Becket. It is also about standing up for what is right in the face of the temptations of power on the one hand and glory on the other. Henry expected Thomas to allow him to exploit his friendship and his church title in order to abuse the power of the Church for the benefit of the State. Thomas refused—a courageous display of not giving into state power’s pressures. Here, Thomas did the right thing for the wrong personal reasons. Somewhere within this narrow interpretation of Eliot’s intention, apparently lay my drunken friend’s epiphany which he claimed changed his life. And who can smirk and presume that he exaggerated that hot morning in Queens?

As a matter of political approach—and unlike T.S. Eliot in his play—I am more interested here in the social aims of King Henry II than in the qualms of conscience of Archbishop Thomas Becket.

In our daily lives many of us do not yet have someone as powerful as Henry II breathing down our necks. But we do face moral challenges. How to say No! at the risk of being different? Join the majority or dare to remain independent? Display your intelligence or be “cool” all-American and act dumb?

As Oscar Romero showed, power struggles are not all the same. But the issues in this play are disturbingly real and perilously relevant to today’s world: man’s nearly meaningless place in the conflicts of this era of authoritarian military-industrial power combined confusedly with the churches of philistine fundamentalism, God-is-on-our-side hypocrisy dominating human affairs.

On the first level, Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral is a play in verse about the dangers of temptations on the way to sainthood or to political power. Thomas Becket resisted several temptations coupled with cajolery and threat. He is offered a return to political power alongside King Henry while at the same time he is accused of disloyalty to the nation and his ecclesiastical office and threatened physically. He is tempted with a return to his halcyon youth with his friend Henry, and the concomitant danger of being forgotten by history.

While Thomas if lured by a return to political power, he also tempted by the glory of sainthood for all eternity. He is offered both the glory of martyrdom and earthly pleasure, both of which he sees as human weaknesses. Not wanting to be “compromised”, he declines the temptation of earthly power. But like Islamic shahids today he allows himself to become God’s instrument and succumbs to the temptation of eternal glory—his fatal weakness: he allows his pride to lead him to a martyr’s death at the hands of power’s executioners: “the right deed for the wrong reason.”

Maybe he did not really seek death but his fate did not permit him to act otherwise. To the tempters he responds with these famous words:

Now is my way clear, now is the meaning plain;

Temptation shall not come in this kind again.

The last temptation is the greatest treason:

To do the right deed for the wrong reason.

One may justly reject the idea that the martyrdom as a religious heretic of Giordano Bruno in Rome or that of Sophie Scholl as a political dissident in Nazi Munich really contributes much to some greater good because man can live a moral life, full of good deeds, without God, and without ultimate sacrifices to a greater good. As Dostoevsky writes: …harmony …is not worth the tears of that one tortured child.

PART TWO

Temporal Power

The temporal power of the Roman Catholic Church refers to the political and governmental activities of the Church as distinguished from its spiritual mission. power.

The Popes of Rome named themselves God’s vicars on earth. The former Papal States in Italy achieved the status of a country with relations with other countries. When on Christmas day in the year 800 the Pope crowned Charlemagne Emperor, the Roman Church gained power over the entire Holy Roman Empire. Church and State were one.

In our times, though officialy separated, Church and State are again often one. Distant from its religious doctrine and its pastoral mission, the Church’s temporal bent is one of its worst aspects which the Church explains is an unavoidable bridge that must be crossed in order to disseminate the Christian faith: earthly power is considered necessary to spread the doctrine of Jesus Christ. In any case, over and over again religions have shown that they have no capacity for temporal power.

We see the proof in practice today in the exercise of power in the USA under the sway of a mystical sort of Americanistic religious persuasion bordering on voodooism infected with the disease of false religion.

As Henry II had done before him, Napoleon abolished the Church’s temporal power and in his conquests dissolved the Papal States as natural rivals for power. Temporal power was then restored to the Church by the Congress of Vienna of 1815 when Napoleonic laws were abolished.

Back in power, the reactionary Church returned to the destruction of modern improvements and reforms, forcing society back to medieval days, for example in Italy banning vaccination against smallpox which then devasted peoples in Papal lands. The Jews were again locked in the Rome ghetto, while the Church’s historic neglect of the environment made of Latium—except for rich Papal estates—the most godforsaken part of Italy.

Finally, in the nineteenth century the new Italian Republic which united the diverse states of the peninsula declared an end to the Papal States. Formally, the Church’s temporal power ended in 1929 with a treaty, the Concordat, between the Vatican State and Italy, according to which the papacy was to have no more political interests in Italy and the rest of the world.

But the meddling of the Roman Catholic Church in temporal affairs has never ended. Its continues to be worldwide. The popes and their bishops pressure temporal society on a wide spectrum of civil issues such as marriage and the role of the family, contraception, abortion, euthanasia, same sex marriage and all progressive legislation. Internationally, the Pope makes statements in favor of peace but carefully refrains from serious criticism of the United States from where come substantial funds to pay for the huge Church bureaucracy. In ethics, the Church line is the “defense of life” in all its aspects, except for capital punishment.

Faith and Politics

Before shifting my point of view to Henry, a few words about Eliot’s faith and a guess at his reasons for writing this powerful text, the second and underlying level of his play. The question is germane. Though Eliot embraced Christianity, the more I get to know him the more I wonder if he really believed. Did he believe in what he wrote here and in his Notes Toward A Definition of Culture? In his play, King Henry only hovers in the background as the representation of Thomas’ past of pleasure, his present of contrast and threat, and the mysterious future. Thomas Becket stands on center stage as if the writer. T.S. Eliot were searching in the Archbishop’s psyche for answers about his own faith—the temptations, doubts and hesitations Eliot the super but uncertain intellectual felt about his faith and his choices.

“Dante in Exile” CC BY-NC-ND by Antonio Cinotti

Among spiritual thinkers and seekers, Eliot returns often to Dante and Shakespeare. Dante, whose universe is dominated by Satan and whose Hell has much more to do with Church and secular politics than religion. Eliot must have known what Thomas-Eliot would say if only he had faith. If only he lived in a world of faith. In the voice of Thomas Becket in the end seeking to purify his motives for accepting martyrdom, Eliot says it: “I have had a tremor of bliss, a wink of heaven, a whisper, And I would no longer be denied.”

Yes, most certainly the writer had his doubts. Not as Dostoevsky, yet, a tremor. A clairvoyant glimpse toward the future. I believe Eliot wanted to believe but I do not believe he even believed he believed. Born to an age of avant-garde thought defined by its rejection of faith in God, Eliot did made faith respectable. Yet his faith seems to have been based on hope. And it was largely aesthetic, prompting Harold Bloom’s remark that T.S. Eliot aspired to the triple identity he claimed of royalist, Christian, and classicist “with considerable bad faith.” In Notes Toward the Definition of Culture written after World War II, Eliot wrote of religion in the USSR some lines pertinent today, especially the last phrase:

“From the official Russian point of view there are two objections to religion: first, religion is apt to provide another loyalty than that claimed by the State; and second, there are several religions in the world still firmly maintained by many believers.”

Or, he might have added, the concomitant danger of conformity of the State to religion as is the case in puritan America.

Lakewood Church in Houston, one of the so-called “mega churches.” (CC BY 3.0)

You can encounter super believers anywhere, those supercilious religious people-bigots who feel superior, convinced that God sustains their actions. The result is their assurance that the wars in Iraq or Afghanistan are holy and that war crimes are just. In their view the just war is a religious war. And in fact, religion is at the heart of many of history’s wars. As a rule, the fundamentalist Fascist State uses religion as a tool to manipulate people. The organized religions through which Power works become malleable tools for perpetrating the crime of wars of conquest. This is not necessarily the fault of the religious impulse in human beings. It is the fault of organized religion itself which today justifies the odious slogans in the USA of “our way of life” and “they (the others) hate our freedoms.” It is the way the self-proclaimed vicars of Christ exploit organized religion.

If not for Eliot’s own religious hang-up, his play Murder In the Cathedral could have centered on politics, not morality and the spiritual instinct. Instead, for a great part the play is seen from an individual religious point of view.

In that sense the murder of Thomas Becket at Canterbury was of less importance for us than the assassination of Archbishop Romero in El Salvador. Thomas’ was in fact more a rogue killing by soldiers who thought they were carrying out what their King wanted done. Maybe Becket died from an act of stupidity—which was most certainly not the case of the murder of Oscar Romero. State power knew exactly what it was doing.

Still, because of the temporal power of the Catholic Church in the England of Henry II, murdering an archbishop was a dangerous act. Not so for the perpetrators in the El Salvador of our times where the hierarchy of the Roman Church stood on the side of brutal imperialist-capitalist power. To Eliot and the modern reader, Thomas’ murder was of much less importance than the democratic belief that not even the king is above the law. For that reason, I believe, Eliot centered the play on Becket’s motives for sainthood, not on his resistance nor on Henry’s potential quest for redemption, and who knows? perhaps the King really hoped for an epiphany. Though the play was written at the time of the rising of Fascism and Nazism in Europe and can be understood also as an individual’s opposition to authority as in the Sophocles play Antigone, Becket’s internal struggle over his opposition to Henry II is in my reading secondary.

Having come into conflict with secular authority, the Archbishop is visited by a succession of tempters urging him alternately to avoid conflict and give in to the King, or, to seek martyrdom. While three priests consider the rise of temporal power, Becket instead reflects on the inevitability of martyrdom, which, though he embraces it, he also interprets it as a sign of his own fatal weakness. Eliot’s Becket thus becomes a Christ figure whose role is the martyr, reflecting the writer’s own quest for faith—aesthetic or genuine, who knows? In any case, Eliot’s Becket is led step by step to provoke violence against himself and to submit to it. Self-murder or suicide? Or martyrdom of both suffering and the resulting glory?

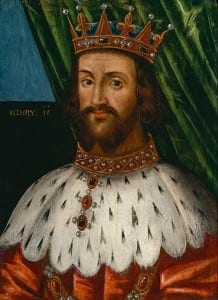

Henry II, Great Grandson of the Norman Conqueror

Henry II via Google Art Project. (Public Domain)

Though the King never appears in Eliot’s play, his shadow is a powerful presence, his power fills Thomas’s past and present. “O Henry, O my King” he laments, while the chorus chants: “The King rules.” Yet though a shadow, the King is human. And state power is real. The priests declaim: “But as for our King, that is another matter.” Or: “Had the King been greater, or had he been weaker Things had perhaps been different for Thomas.”

Though the author T.S. Eliot leaves little room for partisanship, I began to side with the shadow which is King Henry. In real life the King’s struggles against a strong-willed wife and unruly sons and his relationship with his friend Thomas Becket detract from his accomplishments and lasting influence on Anglo-Saxon judicial systems. Eliot however did not favor the King role at all which the Tempter notes when he offers Thomas eternal glory after a martyr’s death:

“When King is dead, there’s another king,

And one more king is another reign.

King is forgotten, when another shall come:

Saint and martyr rule from the tomb.”

Henry II improved the affairs of his kingdom, reaching from Scotland to the Pyrenées. Though he failed to subject the Church to his courts, his judicial reforms endured. His centralized system of justice and modern court procedures replaced the old trial by ordeal. He initiated the concept of “common law” administered by royal courts, thus encroaching on feudal courts and on the jurisdiction of Church courts. He decreed that priests should be tried in royal courts, not in Becket’s ecclesiastical courts.

Henry’s aim was the overthrow of the feudal system, unknowingly to him paving the way for the role of the bourgeoisie and capitalism and making him an active link in Marx’s historical dialectic. To achieve that he had to control the Church by combining under the crown of England both State and Church. Neither Becket nor the faith could stand in his way. He did not eliminate the Church; he absorbed it and used it. For the same reasons modern political leaders of West and East use religion, wrapping themselves in religious language and religious issues—our Christian values, our Christian heritage and God is on our side.

Now, a leap ahead of five centuries to the English Revolution and the three civil wars beginning in 1642. Henry II could not know what he was setting in motion and would have been horrified at the results. For the most radical achievements of the English bourgeois revolution were the temporary abolition and permanent weakening of the monarchy, confiscation of both Church and aristocratic estates. Though not a working-class movement with a revolutionary theory, the English Revolution declared the monarchy “unnecessary, burdensome, and dangerous to the liberty, safety and public interest of the people.” Henry’s impulse resulted centuries later in the execution of the King, a redefinition of the English monarchy and the “dangerous and useless” House of Lords, and the proclamation of a republic.

That is not to say that those 17th century men were particularly foresighted. Still, until recent times western men could see our problems in secular terms because our ancestors had put an end to the use of the Church as a persecuting instrument of political masters.

As long as the power of his state was weak, as Henry II understood, the Church could tell people what to believe and how to behave, as do Roman popes today. For behind the threats and censures of the Church, all the terrors of hell fire are real for its unfree believers-subjects. Under Church control as in El Salvador social and political conflicts become also religious conflicts.

In 17th century England the haute bourgeoisie was terrified of the revolutionary torrent it had let loose. It needed a reformed monarchy responsive to its interests, to check the flow of popular feeling. It also needed the Church of England. The fear then was today’s fear: that the people will rise in revolt in mighty numbers against the rotten capitalist order, which as Marx predicted is indeed rapidly hanging itself with its own rope. As according to Marx religion is the “opium of the people” and is the close and inalienable ally of political power.

A second lesson of the historically under-rated English Revolution was the Revolution’s need for organization. People must choose sides. To decide, they must know what they are fighting for. They learned that freedom of assembly and freedom of speech are the first freedoms to fight for. The ruling bourgeoisie needed the people … yet it feared them. Therefore it kept also the monarchy as a check against too much democracy. The condition of the petty bourgeoisie of 17th century England was similar to that of the former middle class in the USA today, where what was once the middle class, filled with all its false consciousness, is dependent on the corrupt system, dominated and rocked to sleep by the blandishments and rewards given them by the minute upper class.

Therefore, in order to change things, the urgent need for a movement of the lower classes—and an informed and educated class to lead the way—both liberated from the binds of religious fundamentalists in the pay of the system.

Civilizations and cultures have meanwhile gone their own ways, some helped along the way, some hindered. Revolution to revolution, social progress and social setbacks. Who knows if civilization has really peaked and its time is up? While we battle for survival, the question of social evolution remains open. The State-Church equation is different today. The issue is raw power itself, Power in which religion is so enmeshed as to be one and the same with the disastrous results before us.

As Thomas Becket says to the tempter suggesting a return to his past of power and glory, “singing at nightfall, whispering in chambers”:

“We do not know very much of the future

Except that from generation to generation

The same things happen again and again.

Men learn little from others’ experience.

The same time returns. Sever

The cord, shed the scale. Only

The fool, fixed in his folly, may think

He can turn the wheel on which he turns.”