This is an excerpt from Gaither Stewart’s novel, Lily Pad Roll, (Punto Press, 2012), as recorded in the great Russian city of Odessa by the fictional German journalist, Karl Heinz Leonhard.

ODESSA

A light spring breeze from the Sea lifts Antonia’s pink chiffon foulard and lets it first flutter for an instant and then fall gracefully over her shoulder. A frisson of excitement rises in me from my visions formed by remembered film frames from Eizenstein’s great film. As we approach, I don’t permit myself to be tempted by partial views or mere glimpses of the historic scene. I walk with my eyes nearly closed, without so much as turning my head. I want the full impact from film and history, all at once. Then, I open my eyes, and there it is.

“I can hardly believe that I’m standing at the top of the Potemkin Stairs,” I whisper to Antonia. I feel awe. I feel reverence. It was so close all the time and I didn’t realize it. Maybe the stops in Burgas and Varna, in Chisinau and Tiraspol, had also shortened the distances … prepared me for the reality. Maybe that’s the heart of the lily pad idea. Shorten the world. Link it. Mix it. Make it one. Those mad planners still don’t realize the real distances, the diverse peoples, the cultures and the customs involved. They confuse one with the other on their lily pad roll. Makes no difference to them. Other peoples don’t count.

Antonia holds my arm and gazes toward the Sea. A few ripples roll in, hardly more agitated than that first evening in Burgas at the seashore café. The sea breeze is hypnotic, blowing in from the Caucasus, it seems. It’s colder here than I expected. The small boats scattered across the harbor bob only slightly. From this point, the Sea seems pacific. The history behind the scene before us make the reality unbearably beautiful.

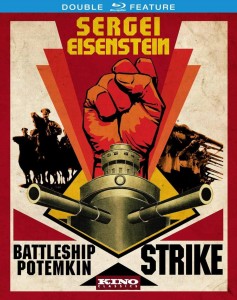

I translate aloud from the guide book in English. Antonia is curious but does not show the same fascination as mine. Though it’s practically her own backyard, she’s never been here. In Odessa. Nor has she seen the Eizenstein film, the story of the 1905 mutiny of the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkin against their officers who fed them rotten meat, then shot many of the sailors for protesting.

It’s a propaganda film. Yet at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958 it was named the greatest film of all time. For cinema historians it is a landmark of cinematography.

“The giant stairway appears like a formal entrance into Odessa from the direction of the Black Sea,” I read. “The stairs are the symbol of the city. They were designed to create an optical illusion. A person looking down from the top sees only the landings from the Sea. From the top the steps are practically invisible. But a person looking up from the bottom sees only steps. One hundred and ninety-two steps and ten stair flights. A secondary illusion creates a false perspective since the stairs are actually wider at the bottom, 21.7 meters, than the top where the first step is 12.5 meters wide. The whole staircase is 27 meters high, extending for 142 meters, interrupted by landings every 20 steps. All together the staircase seen from below gives the illusion of much greater length. Looking up the stairs makes them seem longer than they are and looking down the stairs makes them seem much shorter.”

“The staircase is beautiful,” Antonia finally says almost as in a reverie.

“Come on, let’s go down a couple levels so we can look back up and see it from the perspective of the people demonstrating in favor of the sailors.”

This is the site of the horror scene when Tsarist troops march down the stairs from the top firing point-blank on the mobs of Odessa people on the staircase. At the bottom mounted Cossacks wait, slashing and hacking down the fleeing people with their swords.

I slide into a momentary trance. The guide in one hand, Antonia’s hand in the other, I lift my head upwards, half close my eyes, try to drift backwards in time and into Eizenstein’s atmosphere. The white tunics, the wide belts and black boots of the soldiers standing shoulder to shoulder across the width of the top of the staircase, their identical faces blank, expressionless reflections of blind power, their rifles upright in front of them, their officer with his sword held high, row after row of soldiers in identical formation behind them.

They begin their descent toward us, the officer’s shouted command on the level above Antonia and me, the rifles now lowered, rows of soldiers behind, I drag Antonia down to the next level, shouts of bewildered people around us, terror in the eyes of all, a mother urging her small son to hurry down toward the obscure Sea, the boy stalling, wanting to look at the soldiers, their uniforms, their boots, their rifles, the officer with the sword now pointing downwards, a volley of fire, people falling around us, screams, people scrambling down the stairs they had hardly noted earlier, another volley of fire, an invalid without legs, propels himself with his hands downwards faster than we can run, now volley follows volley, the boy loosens his mother’s hand, she is swept downwards by the terrified mass of bodies, bodies now piling up on each level, along the steps, along the lateral parapet, no way out of the inferno, no emergency exit, only downwards, down, down toward the fatal Sea, the mother, now near us tries to run to her child against the current of human bodies hurtling downwards in a death descent, ever downwards, her son lies on the steps above, she reaches him, picks him up in her arms, cries for help to the advancing soldiers of the vacuous, identical faces and blind eyes of power, another volley and down goes the mother with her son, upside down goes the invalid, a nearly blind woman looks upwards toward the source of the fire until a bullet smashes through her left eye, row after row of soldiers, officers with swords pointed at the people-target, now screams from the bottom of the stairs, “Cossacks, Cossacks” goes up the cry, as power’s savage cavalry slashes and rips and cuts swath after swath among the trapped and helpless people, helpless in the mortal grip of uniformed, armed power, we stand on the penultimate landing and observe the carnage of the people of Odessa dying under the rifles of the faceless soldiers and Cossack swords. Upwards, up toward the horizon, steps, steps, ever more steps, endless steps.

“Karl Heinz, Karl Heinz, stop it, stop it, now, we’re at the bottom,” Antonia says in my ear.

I raise my eyes and see only stairs, climbing and vanishing somewhere above us.

I shake myself back to the present. I’ve read a lot about this film. The theory behind it is simple. Eizenstein wrote that the sailors rising up against their officers and the Tsarist troops massacring the people were emblematic of the Marxist interpretation of the class conflict driving history. The thesis is the bourgeoisie clash with the proletariat; the revolt on the Potemkin and the demonstration on the stairs, create the antithesis, which results in the synthesis in a classless society.

Hence its classification as a propaganda film. But it was the director’s creative genius that produced “the film of all time”. Eizenstein harnessed the popular frenzy of that day in Odessa with his art, used however for revolutionary purposes. The propaganda took nothing away from his art which, combined with the history it related, achieved what Eizenstein said ‘sends the spectator into ecstasy’.

With that film alone he raised the bar high for true art while stimulating class consciousness and prompting the viewer to take up arms in resistance. Unfortunately, in the West, the same technique used to sell capitalist values was easier to achieve than the transmission of values engendering revolution.

Eizenstein loved the long, slow shots and a linear narrative driven by individual protagonists, shots that activate the viewer forced to dwell on one frame—the frame of the baby carriage careening down the steps amid the slaughter, or a soldier trampling the hand of a child, or a mother holding her dying son in her arms—to grasp the symbolism in the action. In contrast, pure intellectual presentation in film or literature bludgeons us with its blunt message devoid of action.

The massacre, the thesis. The mutiny on the battleship Potemkin, the antithesis. The revolution and the overturn of the old society, the attempt at a new society, the new synthesis.

Standing at the bottom of the great Potemkin Stairs, looking up the staircase and then out to the Sea, I mutter that Russia is not as distant and exotic as most westerners believe.

Antonia, the Bulgarian, looks blank. “Distant? Russia? I don’t understand what you mean. It’s right next to us. We drove here in the car. We’re in Russia … more or less. Everybody’s still Russian here. A real Russian city. The home of many famous Russian writers, Babel and Akhmatova and Pasternak. We read them all at school in Burgas.”

She’s right. Even I feel this is Russia. A historical note I came across in my reading came as a surprise because I had assumed that German troops occupied Odessa during World War II. Actually vicious Fascist Romanian troops did most of the dirty work. In retaliation for a resistance attack on the occupation troops in 1941, Romanians massacred 25,000 civilians, most of whom were Jews. In that period more than 280,000 people were deported, including over 100,000 Jews. After 1970, Odessa Jews emigrated to Israel or the USA. Then, after the dissolution of the USSR, Odessa became part of Ukraine. Nonetheless, it remains a very Russian city.

“It’s the propaganda, Antonia. The propaganda you and I grew up with. The fact is the Cold War is still alive. People in the West grow up believing Russia is another despotic Eastern power. Somewhere out there beyond the seas and the deserts. Like the Tartars in the film who never arrive from the desert. They’re only the creation of power to retain control. Now I see Russia is much more part of the West than I realized. Part of us.”

“For Dostoevsky—that’s my major lit course this semester—Russia is a better West … a better Christendom, too.”