=By= Gaither Stewart

Special to The Greanville Post / Updated version

THE DETERMINANT CLASS OF CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAN HISTORY

People are oblivious to the debt the world owes to Russian civilization.

Russia! What a marvelous phenomenon on the world scene! Russia!—a distance of ten thousand versts (about two-thirds of a mile) in length on a straight line from the virtually central European river, across all of Asia and the Eastern Ocean, down to the remote American lands!. A distance of five thousand versts in width from Persia, one of the southern Asiatic states, to the end of the inhabited world—to the North Pole. What state can equal it? Its half? How many states can equal its twentieth, its fiftieth part? … Russia—a state which contains all types of soil, from the warmest to the coldest, from the burning environs of Erivan to icy Lapland, which abounds in all the products required for the needs, comforts, and pleasures of life, in accordance with its present state of development—a whole world, self-sufficient, independent, absolute. (Mikhail P. Pogodin- 1800-1875, Russian historian, journalist, intellectual of the Slavophile movement who held to the Norman theory that the Rus people from whom Russians descended, were Scandinavians.)

Alexander Nevsky (Nikolai Cherkasov) declines a Mongol ambassador’s offer to join the Golden Horde. (Still from the 1938 film of same name directed by Sergei Eisenstein.) Nevsky lived in the 13th century. His main battle, fought on the frozen Neva lake, defeated the invading Teutonic Knights, thereby saving Novgorod, the young Russian nation. The film—overtly and unapologetically politically pedagogic— used a script that had Nevsky utter a number of traditional Russian proverbs, verbally rooting his fight against the Germanic invaders in Russian traditions.

If we are to believe certain oracles of crafty political views, a little revolt is desirable from the point of view of power: “revolt strengthens those governments which it does not overthrow. It puts the army to the test; it consecrates the bourgeoisie, it draws out the muscles of the police; it demonstrates the force of the social framework. It is an exercise in gymnastics; it is almost hygiene. Power is in better health after a revolt, as a man is after a good rubbing down.” Victor Hugo was right, of course. And he is still probably quite correct in his evaluation since the nature of the state has not changed much and probably won’t until it is finally done away with.

(Rome armchair)

It has been said that continuity is the very stuff of history. (1) (Riasanovsky) That being the case, it must be clear that Russia’s historical development shows amazing continuity despite enormous changes and revolutions, invasions and interventions any of which could destroy less powerful cultures.

Since the ninth century A.D. the East Slavs or the Russians we know today have dominated uninterruptedly that great land expanse more than twice as broad as the USA) described by Mikhail Pogodin. Influenced by early Scythians and Sumerians, by Persians, Mongols and Byzantines, the Russians have not only dominated but expanded eastwards to the Pacific Ocean, absorbing the small and disunited local peoples already settled in the Far East who were most likely welcomed Russia.

CLICK ON IMAGE FOR BEST RESOLUTION

CLICK ON IMAGE FOR BEST RESOLUTION

Since the Russians emerged from the Rus peoples of the Kievan state and moved northeastwards, continuity has been the driving force. Kings and princes, Tsars and commissars, Russians all—though today you find many with the slanting eyes of the blood of various eastern peoples flowing through their veins—have guaranteed the necessary continuity to repel repeatedly any and all invaders.

Though the earlier periods of Russian history were dominated by warlike monarchs, the instigators and guides of the march through those open and borderless eastern spaces, also a certain Russian spirit was occupying every vacuum in their path. However, it is impossible to compare that Russian expansionism in those times with the growth and spread of European empires, the earlier Alexandrian or Roman empires with their magnificent military machines and skills, or those which would arise later like Ottomans and Hapsburgs and Hohenzollerns in Europe. The latter empires were amassed by invasion and conquest of existing foreign countries and cultures.

Peter the Great officially renamed the Tsardom of Russia the Russian Empire in 1721, and himself its first emperor.

Since socio-political Russia did not experience an Enlightenment or Renaissance, nor did religious Russia experience a Reformation or a Counter-Reformation as in Europe, its culture took different directions, influenced more than generally recognized by the Mongolian conquest of major parts of Russia, the constant threat of invaders envious of its vast lands, and then later, the reforms of Peter the Great. Thus emerged a culture based on a highly aesthetic-religious format and the pictorial arts, which however spoke a language similar (though with a different message) to that of the great Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals rising across the face of Western Europe, with their pictorial representations translating messages to the illiterate masses of France, Italy and Germany.

In a similar way, Russia’s peculiar form of serfdom held the great masses of illiterate, Russian-speaking peoples in ignorance and wrapped in a world of superstitions, linked to the land of their immediate masters (although they were not quite slaves as in the USA and elsewhere) and in almost religious submission to their “Little Father”, the Tsar. Right up through the nineteenth century the Russian peasant lived a life similar to that of the European Middle Ages, with however certain peculiarities including a powerful attachment to the land and love for their own people that contributed greatly to the Russian character and in the final analysis to the idea of revolution led chiefly by the nineteenth century intelligentsia against the extremely small ruling elite.

The Russian religious philosopher, Georgiy Petrovich Fedotov (b. 1886 in Moscow, d.-1951 in New Jersey), noted that the sky or the heavens is rarely mentioned with particular warmth by the nature-loving Russian Slav. He concentrates his warmth on the earth, the earth as the soil, as a grain-producing field. Thus the great respect for and love for bread.

The subject of the Russian character and the struggle between two small elites—the rulers on the one hand and the intellectuals-intelligentsia on the other marks the history of Russia. While the government cracked down on every manifestation of reform, the Enlightenment in the West had paved the way for Rousseau and Diderot et al, who first attracted cultured 19th century Russians, Westernizers like Alexander Herzen, and a host of Russian intellectuals-exiles, who , step by step, generation after generation, brought also new ideas and culture to the fore in Russia. A long line of Russian intellectuals—writers, historians, sociologist and political radicals, the future revolutionaries—found their inspiration in Paris and London and created the Russian-European sort of men like Lenin, men totally dedicated to revolution, men who hated and mistrusted the Liberals governing Russia so badly following the 1905 revolution— (in a similar fashion to the Russian Liberals of today who would hand their land over to capitalism). Revolutionaries emerged from among those exiles, who though they changed the course of their native land, they also held firmly to the rule of the continuity of Mother Russia.

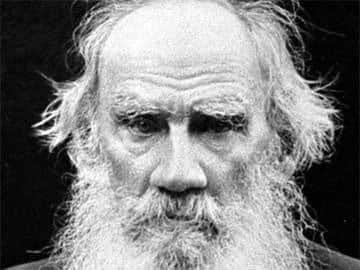

Tolstoy, a giant in any culture, was also pre-eminently Russian by character and vision; he was among the first to put Russia’s literature and intelligentsia on the European map. His esthetic moralism remains a source of light for humanity to our day.

The Revolution, the Civil War, the defeat of foreign interventionists, the dictatorship of the proletariat and the real emancipation of the serfs, NEP (New Economic Policy), Socialism-in-one-country and Stalinism, the education of an entire people, the industrialization of the huge land, the defeat of Nazi Germany in WWII, and the transformation of what was a backward land for the benefit of the elite few into a superpower to counter that of post-World War II USA. If under Tsardom, the driving force of Great Russia was power and the force behind the 1917 Russian Revolution was socio- political, a new, highly politicized breed of post-revolutionary intellectuals had its place in reinforcing the revolution and spreading its message throughout the world: e.g. especially in China and southeast Asia, much of Latin America, and sub-Sahel Africa.

(Moscow, where I felt power)

That new superpower—the land mass populated by staunch Russians linked to those lands, a powerful military machine and nuclear weapons nearly ready—stopped an apparently all-powerful post-WWII America in its tracks in central Europe, an America that preferred to march straight on to Moscow. In a similar manner the new military power of post-Communist Russia has today slowed the advance of aggressive, belligerent, imperialistic America bent on world hegemony. One wonders if Russia can save Europe from America’s mad greed and perhaps even save America from itself.

THE INTELLIGENTSIA

The intelligentsia (a Russian word) and intellectuals, though both engaged in mental labor, are somewhat different. A word imported from Germany and Poland, the intelligentsia is a social-political class which came to be associated with a cultural approach to the world and the existing order in Russia, a class of educated people aimed at shaping a society’s culture and politics. Intelligentsia as a rule refers to a social group, partly political, partly religious or ideological, usually active in some artistic field, but which plays a major role in shaping society, as did nineteenth century Russian members of the intelligentsia class who fashioned the Russian Revolution.

“Prior to the First World War the intelligentsia had become one of the most significant groups in Russian society…..Growing from seeds planted by dissident members of the nobility … who, in the late eighteenth century, had dared to raise their voices in criticism of the inhumanities of serfdom, the intelligentsia had, a century later, become an influential and diverse group. Its basic feature was its impulse to criticise and oppose the fundamental iniquities and occasional barbarities of tsarism. Within this rather loose framework a hundred flowers bloomed. Scientists, painters, authors, professional people, teachers and lawyers in particular, were all represented in the ranks of the critical intelligentsia. A wide variety of types and intensity of criticism could be found from the relatively gentle admonitions of Turgenev, through the penetrating and trenchant parables and sermons of Tolstoy to the fulminations of Bakunin and Lenin.” (2)

The horrific massacre at Babi Yar, ironically very close to Kiev, currently infested with US— and Jewish tycoon-supported Neonazis, should give Jews everywhere, especially in the US and Israel, time for reflexion about their passivity and even complicity in the face of a Nazi resurgence.

A member of the intelligentsia may be of any political persuasion but is more associated with politically committed progressives. In the pre-revolutionary 19th century it was used in Russia by its members themselves also to separate them from the masses. The writer Leonid Andreyev caricatured the intelligentsia as “cut off from the masses … and overstuffed on the bread of the spirit to the point of indigestion, the intellectual (of the intelligentsia, he means) decides global issues and the question of Russia0s existence … but fails in the effort.” In general the Russian intelligentsia has been mercilessly critical of the authorities but forgiving of their own shortcomings. The term has been popularized today and includes also socially-politically narrower intellectuals. In comparison, the pure intellectual too—especially in the West— may engage in arts but more often is a specialist of some kind, especially in the academic field where he/she may or may not feel political commitment, a failure, I believe, of the American academic class. Intellectuals can belong to any ideology: conservative, fascist, socialist and are not necessarily of the intelligentsia.

Film artists and intellectuals congregated around Eisenstein, lured by the promise of the budding Soviet film industry. (Shown: S. Eisenstein in his youth. )

One might claim that Russian intellectuals or educated leadership classes have never succeeded in creating a “culture of continuity” because of the land’s chaotic upheavals. Yet, as shown above, the collapse of the Kievan state and the shift northeastwards of Russia’s center of gravity, the Mongol occupation, Peter’s reforms and the new alternations of capitals between “his” capital of St. Petersburg and Russia’s real capital of Moscow did not interrupt the continuity of Russia’s evolvement. However, never has the concept of continuity of Russia with its past been more obvious than today. Today, with a new model of leadership, Russians in the great metropolises display the same attachment to their lands as centuries earlier. Its so-called Liberals (in cahoots with western imperialists) are simply out of tune with the mood of the nation, people and leadership and are destined to go nowhere at all in mad schemes for Color revolutions in Russia.

(Rome-Paris)

There is an intellectual idea of two types of cultures—one horizontal and the other vertical—proposed by the art historian and intellectual, Wladimir Weidlé. (2) Although there is a great variation in culture and ways of life across Russia, that variation is minimal when compared to the vastness of the territory. The Russian people of the forests of the north and the steppes of the south, in the near west or the distant east, have in general lived a similar life, have similar beliefs and moral ideas. The population of the country of Russia has never been dense, so the question of extension is always predominant here as, I repeat, Russia’s misguided invaders have learned the hard way. Because of that extension coupled with a similar life style, its “horizontal culture”, that is the similar culture that emerged from the masses as in other countries spread over that enormous area.

Vertical culture instead (the culture of genius and the great true works of art) demands that its foundations not be too vast. My conclusion is that Weidlé intended that the great horizontal culture breeds the vertical culture that produces the genius of great art originating as a rule in Russia’s original tiny elite, as happened, for example, in the explosion of the great Russian literature of the nineteenth century, which anyone who has read Gogol, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Lermontov, Chekov, but also a host of other writers, who, it seems, literally erupted in the world almost together. Certainly that sudden literary flowering was a unique cultural phenomenon in the entire world of arts.

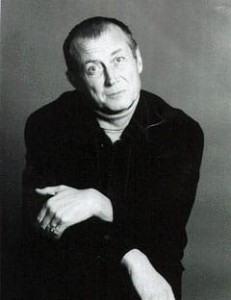

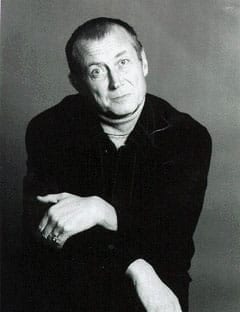

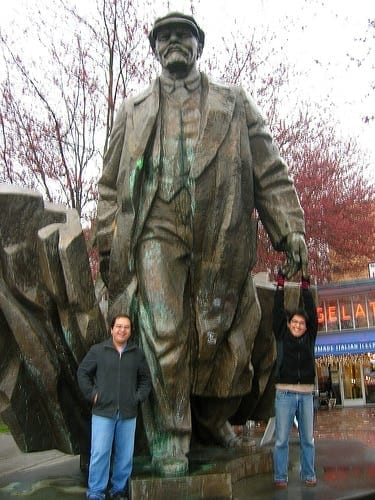

Despite the official arrival of capitalism, Russia still has many people who admire and even revere Lenin, himself a true revolutionary intellectual. Bathed in the political culture of the West—especially the US—where politicians are often crass ignoramuses, people forget that most communist leaders, starting with Marx and Engels, were highly educated, and often could claim a high rank in the world’s intelligentsia. Photo by andresmh

Weidlé’s point was that Russia’s magnificent culture—the pictorial arts, music, ballet and lyric opera but above all its literature—finds its origins and back-up in the horizontal culture, the art of a people of continuity firmly attached to their lands in a uniform fashion unknown in most parts of the world (as experienced by those foreign invaders: the Tartars (Mongols) after centuries were absorbed, Napoleon was defeated ignominiously and sent home to Paris and into exile, the German Nazis were defeated, routed, captured or slaughtered as at Leningrad and Stalingrad and chased the one thousand miles back to Berlin.

It is incontrovertible that the Russian Revolution meant political, social and intellectual revolution. Russian society was transformed into Soviet society according to the plan of Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders. A Soviet man was born. A Soviet culture was created. Despite Pogodin’s enormous land expanse and great variety of ethnic and cultural strains, the Soviet Union became a remarkably homogeneous land that had one official ideology: Communism. In society, one class dominated: Communist. And though workers and to some extent peasants were represented in the Communist Party, intellectuals came to dominate and in turn became a new class. Intellectuals—some honest, some social climbers as everywhere—created Soviet culture, responsible for forming the Soviet Communist person.

The cultural struggles of some intellectuals like Pasternak were quickly magnified by Western propaganda as examples of resistance to a terrible tyranny, which certainly was not the case.

The Soviet performance in science, scholarship, literature, the arts and education is exemplary in its scope, liberal funding, thorough organization, planning and, not least, in party control. Soviet intellectuals were in effect cultural employees of the new state. Creative work in science (Sputniks, the shot at the moon, and Astronauts orbiting the Earth) and music such as that of Shostakovich was brilliant. On the negative side, “socialist realism” in literature, with some few exceptions, was gray and dismal, as were advances in historiography, philosophy and sociology. After the death of the great Maxim Gorky in 1936, few major writers stepped forward. The gifted Alexis Tolstoy and Mikhail Sholokhov managed to write good works in line with party requirements as did the two greats: Boris Pasternak and Alexander Solzhenitsyn, some of whose works appeared first abroad. Others simply emigrated and worked abroad, like Ivan Bunin and Alexis Remizov.

It’s ironic that much in the way Leon Uris’ Exodus left a permanent impression (positive) about Israel on many Western minds, Britisher David Lean’s Dr Zhivago, based on Pasternak’s book, is how many Americans continue to see Russia.

In any case, the now dominant Soviet intellectuals, the new class, became an arm of the new society. Its artists, from Alexis Tolstoy to the great composer Dmitry Shostakovich (his 7th symphony, the “Leningrad” sufficed to make him great), were willy-nilly representatives of the Soviet Russian man.

The Germans thought that sheer brute force and ruthlessness would break the Russian spirit but they were memorably wrong. In photo, a Nazi soldier during the siege of Stalingrad, which turned the tide of war.

As a young man in 1962 in Helsinki for the World Festival of Students and Youth, I was introduced by a journalist acquaintance to the Soviet Russian poet and Russia’s (official) “angry young man”, a man of many arts, Yevgeny Yevtushenko. As one of those representatives of Soviet Russia, with a certain air of deviation about him, Yevtushenko made a tremendous impression on me as we sat in a café booth drinking beer and vodka. At some point he spoke of his sensational poem Babi Yar published the year before about the 1941 Nazi massacre of some 50,000 Jews in a ravine called Babi Yar in the Ukraine capital of Kiev. The first stanza reads:

No monument stands over Babi Yar.

A steep cliff only, like the rudest headstone.

I am afraid.

Today, I am as old

As the entire Jewish race itself.

I never saw Yevtushenko in Moscow but I did meet him once again, this time in Rome, over twenty years later, where I interviewed him on the occasion of an exhibition of his paintings, (which made no lasting impression) held in a wonderful gallery near the Pantheon. Again, he was the enthusiastic but sardonically loyal representative of Soviet Russia that I recalled.

As a journalist in Italy I met, interviewed and befriended other visiting or expatriated Soviet artists: the ballet dancer Nureyev (defected in Paris in 1961) and, a close friend, Alexander Minz, (emigrated to Italy in 1972, also from the ballet world, both premature deaths from AIDS), many dancers from the Leningrad’s Kirov Theater, also the pianist and winner of the Tschaikowsky Prize in Moscow. Yury Yegorov, who emigrated first to Italy in 1972 and then had a career at the Concert Gebouw in Amsterdam in whose apartment we sometimes gathered for a “smoke” after a concert. (He lived in my house in Rome for a short time before moving to Holland where he subsequently died of AIDS at age 34.). At the Venice film festival, I interviewed many Soviet Russian film directors, including Nikita Michailkov. I cite these few but not forgetting many unnamed others such as the hosts of Russian painters exhibiting around the world, who, although apolitical artists, were all brilliant examples of the quality and world influence of the still relatively new Soviet Russian culture.

(Moscow)

To such a people with their vast lands, American “boots on the ground” are not perceived as a great threat. Likewise, NGOs or non-governmental organizations such as anti-Russian Radio Liberty in Moscow itself are a minimal threat and can anyway be forbidden at any moment, which, in my humble opinion, should be done without hesitation. Nor do I believe, I repeat, there will be an Orange Revolution in Russia organized by Russia’s sold-out Liberals, i.e. pro-US, pro-EU , a U.S. Trojan Horse. Russians are after all NOT like West Ukrainian Nazis who wore German uniforms in WWII against Russia and on U.S rose up against their own democratically elected government..

However: NATO troops based or maneuvering on Russia’s frontiers or a US Black Sea Fleet, or a US-run Georgia or Azerbaijan can ignite a nuclear conflict—which neither side negates—conflicts which Russian leaders led by a calm Vladimir Putin handle in a statesman-like manner. The one incalculable to which in my opinion Russia does not give sufficient weight is American Neocon madness, the insanity of persons who themselves do not know what they will do next.

Here I want to develop the above-mentioned, fundamental theme for understanding Russia and Russians: their traditional link to a natural communalism-socialism which is one aspect of their culture, a theme which I hope will not lead modern Russians who might read this to consider my thinking naive. Historians and observers of Russia write of the Russian link to the soil, to Mother Earth, reaching back to Russian paganism, one aspect of folk religion. The other aspect is a sort of “cult of one’s ancestors” which I am tempted to compare to the Mexican tradition, creating a kind of eternal kinship-community, in Russian that extended family is called the rod, something like the Latin gens or the Celtic clan, e.g. the extended family. And in effect the rod is even more powerful than the Russian immediate family which is very close-knit. By way of example, Russians have preserved the patronymic name, the name of the father. All Russians have two personal names, his own given name (Vladimir) and the second a derivative from his father’s name, (Ilich). In folk usage the patronymic, like Ilich, is often used instead of the first name in order to keep alive the chain of the rod. Or the simple Russian might use words of address like “father” or “grandfather”, “uncle” or “brother”, or the corresponding female names. Social life thus becomes an extension of family life. As a result, moral relations among humans are raised to the level of blood kinship.

The Slavophiles conceived of the whole nation as an immense rod, or a people of the extended family. Then the mir, the typical village community throughout all of rural, peasant Russia, though not based on kinship, inherited from the rod the patriarchal form of family. Only one step then separates the Russian rod concept from the Communist idea of mankind as one great family. I cannot hazard a guess as to how many contemporary urban Russians feel that brotherly kinship with mankind today but I think it must be related to the nature of Socialism/Communism as existed in Russia. Dostoevsky like others before him believed that Russia (beauty and love) was destined to save the world. Such thoughts occurred to me personally when a political reporter from Syria recently wrote concerning the Russian military intervention there that it is Russian fortitude that is preserving the world from total war (and the end of mankind)..

(BERLIN)

I once conducted a mini-survey of various persons here who had lived in what was East Berlin before the fall of the wall and the dissolution of Communist East Europe. I recall vividly a middle-aged woman who ran a small shop in the Nikolai Viertel of former East Berlin who with little prompting spoke of how she and many others missed the sense of the closeness of social solidarity—a kind of kinship like the former Russian extended family structure—that had marked the Socialist East, remarks I have heard over and over in East Europe.

This view might seem outdated, even superfluous in our times. But it is not. On the contrary. More and more people of the world have already awakened to the idea that we are all brothers and sisters.

NOTES

1. Nicolas V. Riasanovsky (not an admirer of the Soviet Union or Communism but a lover of Russia) was my professor of Russian history at the University of California in Berkeley in the 1960s. Nicolai Valentinovich Riasanovsky was born in Harbin, then Russian Manchuria, in 1923, the son of a lawyer and the novelist Antonina Riasanovsky, who wrote under the name of Nina Federova. The family moved to the USA in 1938. Nicolas died in Oakland, California, adjoining Berkeley, in 2011. His major works included his best-selling History of Russia, and Russia In the West In the Teaching of the Slavophiles. His obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle: “He, Riasanovsky) specialized in the reign of Emperor Nicholas I (1825 to 1855), a period he examined from different perspectives in a half-dozen books focusing on the monarchy itself, the emergence of state-sponsored nationalism…..His writing was known for its scrupulous examination of perceptions and misperceptions on all sides in unfolding events. But when Professor Riasanovsky decided to write a textbook for undergraduates in the early 1960s, he was motivated at least in part by concern with the perceptions that Americans had about Russia.”

2. Christoher Reed, History Today, Volume 34, 10 October 1984

3. I became acquainted with Professor Weidlé interviewing him in Paris in the 1960s. (Vladimir Vasilyevich Veidle, b. 1895 in St. Petersburg, d. in Paris in 1979), an art and literature historian and critic, Veidle taught in Perm after the revolution before emigration to France in 1924. I had the privilege of meeting him several times in Rome where he came each year on a kind of pilgrimage “to visit Caravaggio”, always staying in the same Plaza Hotel on Via del Corso where everyone called him “Professore”, and each year visiting the same artists. In the longest church art visit I had ever made he showed me and lectured in detail in a wonderful mixture of French and Russian the wonders of the Church of Santa Maria del Popolo, parts of which by Bramante and Bernini and not only two major works of Caravaggio, but also Pinturicchio, Raffaelo, and many other artists of the Rinascimento. His books on Russian culture are still available.