=By= Gaither Stewart

AMULET A Political-Fantasy Novel by Roberto Bolaño

As read and admired by political novelist Gaither Stewart

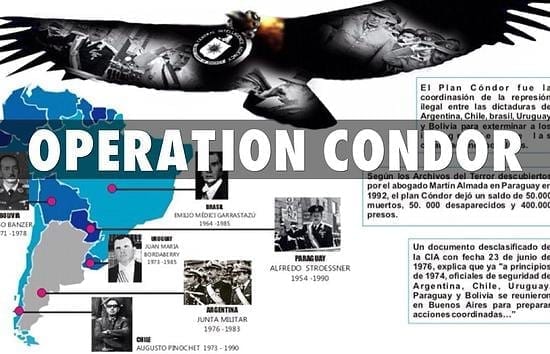

I am reading for the first time the work of Chilean born writer, Roberto Bolaño. His novel, Amulet, set in a phantasmagoric Mexico City that, perhaps, also because it is Latin America’s biggest city, represents the entire crushed and tortured and imprisoned and murdered Latin America while also his characters are emblematic of the suffering and decimation of much of the best of the Latin American youth. Perhaps the author chose to highlight Mexico City, not only because of the massacre of Mexican students there in 1968, but also because he moved there as a teenager and lived there many years before moving to Spain and Barcelona where he died at 50.This distinct novelist-fabulist, Roberto Bolaño, depicted in his Amulet the systematic U.S. – organized political disasters (Operation Condor) in Latin America in the 1960s and 70s. Bolaño was a literary writer who attempted to correct official governmental history such as that of the Chilean revolution and its crushing by the counter-revolution of General Pinochet and Operation Condor, as well as the massacre of Mexican students by government police and army on Plaza Tlatelolco in Mexico City The narrator of this fable is the author’s dream-like Auxilio Lacouture who, when the riot police and soldiers arrive that day in 1968 and arrest everyone, hides in a stall in the women’s bathroom of the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature in the National Autonomous University of Mexico where she remains alone and without food for thirteen days, eating only toilet paper until all hunger passes and with time becoming a Mexico City Legend. During those interminable days and nights on the cold tiles of the bathroom she dreams and imagines the characters and actions of Bolaño’s fable about the young poets of Mexico City and Latin America.

Graphic by Merit Freeman

In the first chapter of AMULET, Auxilio, young herself and beautiful except for four (unexplained) missing front teeth, who calls herself “the Mother of Mexican Poetry” relates of herself after her arrival in Mexico from Uruguay or perhaps from Buenos Aires (facts here are always elusive and uncertain) when she goes to work for free for two older and famous Spanish poets, although she has no money, no official work, and often no fixed residence:

“… Auxilio, leave those papers alone (the two Spanish poets would say), woman, dust and literature have always gone together….” How right they are, dust and literature from the beginning …and I conjured up wonderful and melancholy scenes, I imagined books sitting quietly on shelves and the dust of the world creeping into libraries, slowly, persistently, unstoppably, and then I came to understand that books are easy prey for dust….However heroic my efforts with broom and rag, the dust was never going to go away, since it was an integral part of the books, their way of living or of mimicking something like life.”

Unexpectedly I stayed longer than anticipated in chapter one, in fact I moved backwards when early on I saw that this book requires much repetition and much interpretation. For this is a very political novel, a criminal act for many readers for which crime I have lost friends, though Bolaño covers it up well, not only with brilliant writing but through his strange heroine Auxilio Lacouture, the “mother of Mexican poets” some of whom she sleeps with and who do not mention her missing four front teeth. The author disguises the political also with love and with travel. One day Auxilio leaves Montevideo for Buenos Aires across the Rio de la Plata and then travels on to Mexico, her destiny she says, in search of two Spanish poets living in Mexico City.

“Maybe it was madness that impelled me to travel. It could have been madness. I used to say it was culture. Of course culture sometimes is, or involves, a kind of madness. Maybe it was a lack of love that impelled me to travel. Or an overwhelming abundance of love. Maybe it was madness…..

“You run risks. That’s the plain truth, and even in the most unlikely places, you are subject to destiny’s whims.”

In Bolaño’s prose, objects come alive and play major roles. Auxilio becomes obsessed by a vase her god-like poet stares at. She stares at it too and comes to fear and hate it and wants to smash it on the floor but is afraid to touch it, certain it contains hell in its depths. Over the years, lost books, dead poets, then love dissolve into the air of Mexico City and perhaps become part of the dust that blows through the city.

“The dust cloud reduces everything to dust. First the poets, then love, then, when it seems to be sated and about to disperse, the cloud returns to hang high over your city or your mind, with a mysterious air that means it has no intention of moving.”

Bolaño works in images. Mostly created by his fantastic characters, some independently and deeply buried in the at times arcane text. He uses repetition to make his point. The two chief images are the massacre of Mexican students on Mexico City’s Plaza Tlatelolco by the state (during which thirteen days Auxilio remains locked in her stall in the women’s bathroom on the fourth floor of the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature of the National Autonomous University of Mexico) and the crushing of the democratically elected leftwing Chilean government of Salvador Allende in Santiago by Operation Condor/General Pinochet. Repetition, Repetition.

They are all young, seventeen, eighteen, nineteen years old, the “young poets of Mexico City” with whom Auxilio, the Mother of Mexican poets, hangs out all night in the bars of Colonia Napoles and Colonia Roma and in chic Colonia Polanco or in the Zona Rosa or she visits someone in very elegant Coyoacan as well as in many of the city’s “incurable streets”, but above all in the bars like the author’s Café Quito on Avenida Bucareli and they are poor but they are not all really Mexican. They are all of Latin America. They are positive youth, the best, in contrast with the other group hanging out in the same bars, referred to as “old, failed journalists” and Spanish exiles, friendly people but not good company, all engaged in the same old conversations such as their stories about Fidel and Che Guevara during their stay in Mexico. No one is satisfied with the answer of a very sexy female character named Lilian who was very beautiful when she was younger, who says she slept with Che and that in bed “he was normal.” “Lilian was Mexican …. It was said that in the course of her drawn-out youth she had many fiancés and admirers. Lilian, however, was not interested in fiancés, she wanted lovers, and she had them too.” She liked nothing better than lying in bed with a man and moaning with pleasure till dawn. That too is Bolaño. El Che in bed could not possibly be just normal. Other accents enter the individual stories, Uruguayan or the Porteño of Buenos Aires or Chilean and mentions of Ecuador and Honduras and Nicaragua and Panama. The reader gradually comes to realize that these poor, bedraggled, homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual, faceless, nameless, unidentified youth are the lost generation(s) of all of martyred Latin America.

On October 2, 1968, in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco section of Mexico City, Mexican riot police and military forces massacred hundreds of students and civilians to suppress the growing student protest movement centered at the National Autonomous University of Mexico—ten days before the opening of the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City which were not to be disturbed. These events were part of the Mexican Dirty War when the government used all its forces to suppress political opposition. Thousands were arrested, beaten and tortured by security police. There is no consensus on how many were killed that day in the plaza area. At the time the government and the mainstream media in Mexico claimed that government forces had been provoked by protesters shooting at them. But official documents made public since 2000 suggest that the snipers had been employed by the government. If this makes you think of Kiev, Ukraine, in 2014, it is because it is the same U.S.- organized Dirty War. Same formula. Same dead youth. False flag in 1968. Estimates of a death toll from 30 to 300 contrasts with eyewitnesses reporting many hundreds dead, their bodies stacked in huge piles.

As Auxilio hallucinates in her stall-home in the women’s bathroom of the National Autonomous University of Mexico Faculty of Philosophy and Literature she ruminates about her relationship with the children of the sewers, from the darkest, dirtiest places of Mexico City, i.e. of all of Latin America and to the small voice that is her herself she launches into a series of connected-disconnected prophecies of the reincarnation of the greats of literature: “These are my prophecies, Vladimir Mayakovsky shall come back into fashion around the year 2150. James Joyce shall be reincarnated as a Chinese boy in the year 2124.Thomas Mann shall become an Ecuadorian pharmacist in the year 2101. For Marcel Proust, a desperate and prolonged period of oblivion shall begin in the year 2033. Ezra Pound shall disappear from certain libraries in the year 2089….

“Luis Borges shall be read underground in the year 2045….Virginian Woolf shall be reincarnated as an Argentinean fiction writer in the year 2076. Louis-Ferdinand Céline shall enter Purgatory in the year 2094. Paul Eluard shall appeal to the masses in the year 2121.” And the writer-Auxilio-Mother of Latin American Poets continues through some Italian and French literary greats before coming out with predictions like: “Framz Kafka shall once again be read underground throughout all of Latin America in the year 2113….

“The case of Anton Chekhov shall be slightly different: he shall be reincarnated in the year 2003 (the year of Bolaño’s death in Barcelona), in the year 2010, and then in the year 2014. He shall appear once more in the year 20181. And never again after that.”

The connection of these two pages of literary prophecies with the rest of the text of this book is a riddle. Do the names selected have significance? Do the years for their reappearance, underground life, the alterations in their vocation have meanings? I myself will leave these considerations to others and pass on to the novel’s final and for me most meaningful passages.

In the story’s last and most powerful scene, in which Auxilio has imagined she is descending from the frozen heights of snow and ice of Machu Pichu toward the valley, abandoning her stall in the women’s bathroom of the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, thinking of the legend borne on the winds of 1968 that circulated among the dead and survivors, and that now everyone knew that “when the university was occupied in that beautiful, ill-fated year, a woman remained on the campus …”. And when people said that I was the mother of Mexican poetry I would say that “I’m nobody’s mother, but I did know them all, all the young poets, whether they were natives of Mexico City, or came from the provinces, or other places of Latin America …and I loved them all.”

And Auxilio endured and left the immense regions of snow and ice and saw a great valley opening below. And then she saw that at the end of the valley it opened into a bottomless abyss. The valley led straight into the abyss, And then she saw a shadow spreading and advancing from the other end of the valley and after a while she realized that the advancing shadow was “a multitude of young people, an interminable legion of young people on the march to somewhere….

“I also realized that although they were walking together they did not constitute what is commonly known as a mass: their destinies were not oriented by a common idea. They were united only by their generosity and courage…..

“They were walking toward the abyss. I think I realized that as soon as I saw them. A shadow or a mass of children, walking unstoppably toward the abyss….

“And I heard them sing. I hear them singing still, faintly, even now that I am not in the valley, a barely audible murmur, the prettiest children of Latin America, the ill-fed and the well-fed children, those who had everything and those who had nothing, such a beautiful song it is, issuing from their lips, and how beautiful they were, such beauty, although they were marching deathward, shoulder to shoulder…. The only thing I could do was to stand up, trembling, and listen to their song … right up to the last breath, because, although they were swallowed by the abyss, the song remained in the air of the valley….

“So the ghost-children marched down the valley and fell into the abyss. Their passage was brief. And their ghost-song or its echo, which is almost to say the echo of nothingness, went on marching….

“And although the song that I heard was about war, about the heroic deeds of a whole generation of young Latin Americans led to sacrifice, I knew that above and beyond all, it was about courage and mirrors, desire and pleasure.

“And that song is our amulet.”