The Trojan Spy

Publisher’s Preface

By Patrice Greanville

The Trojan Spy, is the first title to be published by Punto Press, a new publishing company associated with The Greanville Post, and dedicated to advancing radical political thinking and social change. I do hope that the reason we inaugurated our publishing venture with this book (technically a work of fiction, albeit far more than that, authored by our own senior editor and European correspondent Gaither Stewart) will become clear as you read this introduction.

Kim Philby: the undefeated spy who “did it” for a cause. No regrets.

If you find it engaging and persuasive, consider purchasing the book. It’s not only a great read, but also a meditation about spycraft and about the sordid shenanigans of the leading powers’ intelligence and police services that continue to play ever more important roles in deforming reality and shaping history to the benefit of the world’s plutocracy. The exploitation of fear and terror was seen even in colonial days by our founding fathers as a sure but devious method for yoking the people to a false democracy. Today, with modern tools and horrendously large propaganda machines that encircle the globe, the fabrication of fear and terror, and its concomitant strategy of tension by the ruling circles is far more easily accomplished. Such program of manipulated perceptions is stampeding the public into a new breed of slick authoritarian regimes that, unless stopped, will soon eviscerate every remnant of authentic representative government. As things stand, the first nation to fall into this trap is likely to be the United States.

•••••

WHAT MAKES THE SPY TICK? In a book seriously devoted to undercover agents and the repercussions of their actions, the question merits some consideration.

Despite the complexity we find in human affairs, spycraft is an occupation with a rather narrow range of causality, aptly summed up by the pros in the mnemonic “MICE”. Indeed, a surprising number of spies and defectors seem motivated by nothing loftier than money (the “M” in the acronym). Many more, of course, join up out of idealism (the “I”), of which “patriotism”—so often a primal, manipulated emotion rooted in tribalism—could be regarded as a bastardized subset. Others—as the record shows—have been recruited through coercion (the “C”), following entrapment or sexual blackmail, or by threats to their families or friends. Still others join for personal reasons (ego, the closing “E”)—such as racism, revenge for crimes inflicted or imagined, thirst for adventure, and, in a significant percentage, silent disenchantment with a given ideology. Some spies naturally incorporate in their makeup a combination of several factors.

In this framework no segment seems to have had an uncontested superiority in terms of productivity, albeit steadfastness has normally been the province of idealists. Still, while lacking the possibly redeeming rationale of those who betray out of principle, the mercenary crowd has left a heavy imprint on history.

Elyesa Bazna (incarnated by James Mason in the memorable thriller Five Fingers), an intrepid Albanian working as a valet for the British ambassador in Turkey during WWII sold critical secrets to the Germans. The material was so sensitive that, had the Nazis acted on the information, the allies would have paid a much higher price to defeat Hitler. And Bazna was hardly the only one risking his life for money in that conflict.

The FBI was not exempt.

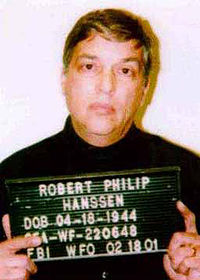

With the start of the Cold War, new opportunities opened for those who saw the selling of key secrets as a fast track to a hefty bank account. CIA operative Aldrich Ames, one of the most prolific, specialized in selling the identities of CIA agents placed within the KGB to the KGB. He reputedly betrayed no less than 100 agents. Matching Ames’ industriousness, Robert Hanssen, a former FBI agent, spied for Soviet and Russian intelligence services against the United States for 22 years (1979 to 2001). During his espionage career Hanssen compromised scores of investigations and operations, including the surveillance of suspected mole Felix Bloch. And then there was Navy communications officer John Walker, Jr. who in 1967 snuck into the Soviet Embassy in Washington, D.C., and offered to sell secrets. He then handed over settings for the KL-47 cipher machine, which decoded sensitive US Navy messages. His motivations were strictly financial, and he proved to be a screaming bargain: over the next 17 years, Walker gave the KGB the locations of all American nuclear submarines, as well as the procedures the US would follow to launch nuclear missiles at the Soviet Union in the event of war. The Soviets also learned the locations of underwater microphones tracking Soviet nuclear submarines. Moreover, KGB agents learned every American troop and air movement to Vietnam from 1971-1973, and they passed this on to their allies, including the planned sites and times for U.S. airstrikes against North Vietnam. According to Vitaly Yurchenko, a KGB defector, “It was the greatest case in KGB history. We deciphered millions of your messages. If there had been a war, we would have won it.”

***

Money can certainly buy favors, but astonishing as this record is, it is the “idealists” who usually capture our imagination and, for many, reluctant or frank admiration. One reason is that idealists have complex, even noble motives for their actions, and these motives are usually rooted in visions grander than squalid pecuniary interest. It was idealism that made the members of the Red Orchestra (more on that later) risk their lives right at the core of Nazi Europe. And it was obviously idealism, a firm ideological commitment to what they regarded as a better social and political order that turned a handful of privileged British youths into formidable spies for the Soviet Union. I’m speaking of course of the famous “Cambridge Five” of whom the charismatic Kim Philby was perhaps the most notable member. To this day, they remain in a league of their own.

Anthony Blunt: As close to the royal family as you can get.

Converted to communism during their years at Cambridge University, the group, which served Soviet intelligence from the 1930s thru the early 1950s, also included Donald Duart Maclean, Guy Burgess, and Anthony Blunt, all with solid establishment credentials (Blunt was demonstrably a cousin of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, the late Queen Mother.) British intelligence officer John Cairncross (the only one with proletarian origins) was also suspected of being a member of the ring, the elusive “fifth man”, but his membership and double-cross remained officially in doubt until supposedly confirmed by KGB defector Oleg Gordievsky in 1990. 1

The discovery of KGB moles at the top of the British SIS (MI6), and the decision of the Cambridge Five to “betray Crown and country” shocked, embarrassed and confounded the establishment. Inexplicably, or rather very explicably, the vetting had failed: the five were not only avowed Marxists, but, rubbing salt into the wound, several—Burgess and Blunt—were open homosexuals, the first flamboyantly so, while Maclean was thought to be bisexual. Homosexuality has long been a “red flag” to paranoid bureaucracies, in the secret service perhaps even more so, and yet all of this was happening at a time when homosexuality was also a crime in Britain. Compounding the insult, it was clear any decent investigation would have turned up former membership in the Cambridge Apostles, a Cambridge clandestine discussion group of 12 undergraduates, mostly from Trinity and King’s Colleges who considered themselves to be the brightest minds in the university. The members scarcely hid their contempt for the decadent capitalist democracies, a disgust that later crystallized into full-fledged loathing and alienation when France, Britain and the US failed to assist the Spanish Republic in its hour of need, and offered little prospect of standing up firmly to an aggressive fascism. In their eyes, only the Soviet Union would and could do that. In that sense, the Cambridge Five were already defectors from “bourgeois” democracy, or “premature antifascists”, when the first Soviet controller, Arnold Deutsch, approached them. But the question lingers: why did the British SIS accept such men despite their easily verified left leanings? In my view herein lies a lesson, a lesson that may no longer apply but which bears mentioning. As far as the British recruiters were concerned, maybe they simply acted out of allegiance to a dying social code, fealty to a waning empire in which the “old boy” network and class reigned supreme and shabby matters like verifying the loyalty of a gentleman were perceived as redundant if not downright insulting. In such manner class may have trumped adherence to discipline in security procedures. The snake bit its own tail.

Of course, that’s not what officialdom and their hangers on in the press said at the time. But whatever reasons the SIS had to admit such improbable candidates to its inner sanctum, the establishment still had to produce a palatable explanation for their betrayal. Critic Ann Talbot, an avowed socialist and a perceptive student of John Le Carré, has advanced a compelling interpretation of how, in his usual elegant fashion, Le Carré performed a cathartic function for his class, while avoiding a Marxian conclusion:

“As far as every Englishman of a certain class is concerned, le Carré has explained to them why men of their own social standing could betray them to the Soviets.

Burgess, Philby, Maclean and Blunt, the Cambridge spy ring, have left a scar in the consciousness of the English ruling class that still stings. They could not penetrate the mystery of how boorish communists had turned men who had been to the same schools as them and were members of the same clubs, into Soviet agents.

Le Carré’s novels offer the British ruling class a sense of absolution by converting the affair of the Cambridge spies into a moral failure, into a betrayal that could be traced back to a childish insecurity incurred in the nursery. Le Carré’s “virtue” is that he can explain this betrayal in terms of individual, moral failure, because at bottom, he is like the traitors. In his BBC interview he confessed, or boasted of, a similarity between himself and Kim Philby. Both, he said, came from disturbed and questionable backgrounds in which their fathers had been—shame of shames—sometimes unable to pay the school fees for their sons’ private education. Le Carré’s father was a conman who kept one step ahead of the law. His home life was chaotic. Like Philby, le Carré responded to this embarrassment by becoming the quintessential high church Anglican Englishman. They both sought the emotional security, which they lacked at home, in the bosom of the church and the English establishment. But the establishment had, like his father, betrayed Philby. His country had sold out to the Americans and so he turned to the Russians, who seemed to offer some alternative to the all-pervading influence of American capitalism, some separate European perspective.

To see events in this light is in some sense comforting, since it obscures what impelled the Cambridge spies to throw in their lot with the Kremlin. During the 1930s significant layers of liberal thinkers in Britain and around the world, including the alienated sons and daughters of the ruling class, were attracted to the Soviet Union. Some had vague feelings of sympathy for the achievements of the October Revolution. Others were horrified by the growth of fascism and the threat of war, and … saw the Stalinist regime as a bulwark against this danger—one which also offered an alternative to naked class conflict at home through its profession of support for the “people’s front” against fascism … In Tinker Tailor, Soldier Spy and Smiley’s People le Carré offered an explanation of how this betrayal could happen. His was an answer that lay not in politics or the iron logic of economics, but in individual psychology, in the ‘human condition’.” 2

Yes, as Talbot suggests, the odyssey of the Cambridge Five has been a godsend for the espionage genre. Fans of John Le Carré will easily recognize in several of his plots the physiognomies of one or more members of the ring. Specifically, Le Carré depicts and analyses Philby as ‘Bill Haydon’, the upper-class traitor, code-named Gerald by the KGB, the mole George Smiley hunts in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, one of his most accomplished novels. (So accustomed may Le Carré be to the spy world’s hall of mirrors and lies that he makes Haydon if not totally gay at least bisexual. In real life Philby, an effortless seducer, was the only member of the Cambridge Five unswervingly heterosexual, even, some would say, to the point of promiscuity.)

***

We spoke earlier of idealism as being a powerful motivator for spies and defectors. If so, how did these spies see themselves? Enough is known by now to support a few conjectures. First, it’s true that in the formal, technical sense these men were guilty of treason. But, we must ask, treason to what? Even UNO and US statutes regard noncompliance with criminal orders a moral duty exempt from punishment. What of a criminal system? What if these men thought that the capitalist system—a system whose real corrupt face they had come to know from within, from their upper class perch—had deceived them first, and that their acts were simply an instance of delayed “allegiance rectification”, albeit one on a much larger scale? Can loyalty ever exist in a moral vacuum?

Judgment can be passed, but it remains a risky exercise. If war teaches us anything it is that great valor and millions of lives can be and have been repeatedly wasted—sacrificed is the more precise term—on the altar of misguided causes. Surely no one in his right mind can believe that the millions who fought in the Confederate armies, or the Nazi legions, serving heinous objectives, or who today serve the Anglo-American imperial ends in all latitudes are or were all morally bankrupt, ethical morons for whom evil was as natural as breathing, and honor a complete mystery. Many cases of honorable behavior, decency, compassion, even, have occurred and do occur in all armies. For when it comes to men’s reasons for action, including risking their lives, the mix is confusing, and misguided idealism, a subjective choice that may or may not accord with what most sane and decent humanity regards as “objectively moral” is a very real possibility. In an age of widespread false consciousness perhaps more so. With this in mind why isn’t it possible that the Cambridge Five came to see loyalty to Britain, monarchic, capitalist and imperialist, as a case of profoundly misguided loyalty by their peers?

The final irony is that, for all their troubles, the Cambridge Five were not entirely trusted by their Soviet controllers. The information was too good, and the boys had been recruited much too easily. What if they were a British plant? A bunch of double agents? What if their allegiance still lay with Britain and her decrepit bourgeois way of life? After all, the feeding of true information is a well known tactic to create trust on the opposite side, all the more to eventually make them swallow the big poisoned hook. That was exactly Stalin’s take on the matter, a viewpoint that inevitably led to endless checks and double checks on whatever the Philby group submitted, to the point of near paranoia. Except that near paranoia is a normal state of affairs for any self-respecting intelligence service.

Philip Knightley, who knew, liked, and interviewed Kim Philby in his Moscow exile, and who certainly understood a thing or two about spies and their trade, had this to say:

“The conclusion from all this is that the main threat to intelligence agents comes not from the counter-intelligence service of the country in which they are operating, but from their own centre, their own people.

In a dirty bogus business, riddled with deceit, manipulation and betrayal, an intelligence service maintains its sanity by developing its own concept of what it believes to be the truth. Those agents who confirm this perceived truth—even if it is wrong—prosper. Those who deny it—even if they are right—fall under suspicion.

From that moment on, the better that agent’s information, the greater the suspicion with which he or she is treated. When other agents offer confirmation, the suspicion spreads, until the whole corrupt concern collapses, only for a new generation of paranoid personalities to start afresh.

Knowing this, anyone interested in the spy world should reflect on the moral problems of espionage, and how they might be confronted.” 3

***

Ah, morality. The elusive imperatrix and judge of our actions. The quiet and patient tormenter of those who, once blessed with a conscience, break her rules. Spies, too, have consciences, of course, and a sense of honor, so, barring the absolute sociopaths, gaining someone’s confidence and betraying it is no trivial matter. This is the natural crux of most “mature” spy fiction. Quite properly, then, that it’s the uneasy, ever-changing tension between trust and betrayal that fuels the narrative in Gaither Stewart’s absorbing The Trojan Spy, the first installment of his Europe Trilogy, an espionage yarn with a unique sort of spy at its center: Anatoly Nikitin. Through this trilogy Stewart aims to go further and higher than most storytellers, into an exploration of the meaning of allegiance to a wrong but pervasive ideology.

“In The Trojan Spy some of his followers accompany him, already an old man, in his battle against the hidden powers behind terrorism. Other characters influenced by Nikitin emerge and assume protagonist roles in the following two novels, Lily Pad Roll and Time of Exile, which together with The Trojan Spy form the Europe Trilogy. In each book some characters vanish, swallowed up by harsh happenings on the world stage; new ones replace them, too. In one way or another each of them seems like a creation of Anatoly Nikitin. [And] though The Trojan Spy is considered a spy novel, Lily Pad Roll and Time of Exile change categories and delve into the chicanery and machination of corrupt and degenerate power today, in effect showing the dark side of the New World Order, which threatens the existence of planet Earth.” 4

To fill this canvas, in Anatoly Nikitin, the double (or is it triple?) agent with his own unexpected (some would say Quixotic) agenda, Stewart paints a man initially trapped by the “spy’s disease”, the corrupting sense of exceptionalism that permeates the profession, and who is later liberated by the blossoming of a moral conscience. For Nikitin, who would probably prefer to see himself as simply a skeptic or a cynic, is that unusual kind of man: a moral spy, a spy for grownups.

The idea of an “ethical spy” may strike some as an oxymoron. After all, in popular culture we have been conditioned to believe that spies are unidimensional entities, “good” or “bad” depending on which side they are on (ours always good, of course), but the type of people who, like politicians, much too frequently thrive (and depend for their success) on ruthless opportunism. How can that be reconciled with a temperament guided by moral rectitude?

Indeed, as one delves into the volume’s first chapter it quickly becomes clear that Stewart did not set out to write these books with mere entertainment as his primary goal, nor to supply the market with one more spy thriller, although the reader will hardly lack for fascinating characters and gripping twists and turns in a plot which, at its core, packs a searing indictment of an entire system. Fact is, The Trojan Spy is a novel that effortlessly rises to the top of its class where perhaps only two other authors, John le Carré, with his Karla Trilogy, and Graham Greene with his “Greeneland” oevre, can share the distinction of mining the genre to its fullest dramatic, literary and even, I daresay, spiritual potential.

But while Le Carré’s spy tales are chiefly focused on the intricate mechanics of the competing services locked in a manichean universe in which the clash of the capitalist West and the socialist East tend to become mere backdrops to the protagonists’ fatalist dance (Le Carré only began to question his previous Cold War certainties in 2001, with The Constant Gardener); and while Greene’s plots, faithful to his Catholic view of the world, probe incessantly the struggle between salvation and damnation, sin and divine grace, Stewart’s ultimate focus is the threat posed to a unipolar world by an amoral malignant corporatism.

As we have seen, morality is indeed the fulcrum of a lot of spycraft, of the humint kind, that is, the information gathered and deeds perpetrated by special flesh-and-blood agents and not merely sophisticated machines or sinister satellites stealing secrets and robbing lives with impunity from the invulnerability of outer space (the kind that corporatism now increasingly uses). It is also at the heart of many an agent’s dilemma: the old question of loyalty and treason, and the commitment to a higher cause that may justify the crosses and double crosses and even triple crosses that such duties could require.

Writers who prefer these kinds of “deeper themes” are rowing against a fierce current these days, although the origins of the situation go back several decades. Why this has some importance in the present context, and how this relates to the Europe Trilogy I have tried to show below.

***

Movie Critic Peter Howell has nailed the problem right on the head, when he says, referring to a recent Tom Cruise actioner blockbuster:

“Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol may blow up things real good, often without much purpose, but Tinker Tailor finds the most devastating detonations resonate deep within the soul.” 5

The deterioration of the spy thriller has now entered a crisis. But this is a crisis that, to paraphrase Garcia Marquez, has been long announced.

Even Ian Fleming’s formidably seductive agent, 007, the James Bond first immortalized for world audiences by Sean Connery (the film versions eventually influenced Fleming himself in how he depicted Bond), is a two-dimensional figure at best, a comic book idea of an intelligence agent (the archenemies even more outrageously so). And in recent years, the genre has slid further down the fantasy hole, albeit one characterized by a new twist, typical of the new artistic and technical freedoms offered scriptwriters and directors by the new digital and stunt technologies, something that we can only describe for lack of a better term as faux hyper-realism. Thus today’s Hollywood actioners are sensorial assaults where the suspension of disbelief is utterly reinforced by the sheer verisimilitude of the images presented. As well, reflecting the new world conditions, this new breed is more cynical, and less shame-faced about US operations.

In the end, these deafening concoctions brimming with death-defying acts, gratuitous violence, and absurd plots so transparently designed to offer plenty of bang-bang and “wow moments” to juvenile audiences blot out all remnants of plausibility. That—as I argued earlier—inevitably corrupts the writers, even those whose artistry is solidly established. In Robert Ludlum’s celebrated Bourne series, gimmicks dominate the plot. The hero, a super CIA assassin rendered personable in films by Matt Damon’s charisma, suffers from identity amnesia! He’s also invested with what can only be defined as autistic-grade linguistic powers: His skills, besides expertise in hand-to-hand combat, firearms, explosives, handling numerous types of vehicles (land, air and submarine, of course), include speaking fluent English, French, Dutch, Russian, German, Spanish, Czech, Polish and Italian. We shouldn’t be too shocked if in the near future we also find him directing the New York philarmonic.

But such novels (and Hollywood’s further adulterated depictions of real undercover agents) typically miss the far more complex and captivating truth about such people, a truth that begins with the simple realization that most spies—at least in peacetime—are plain human beings living or pretending to live pretty mundane lives (when behind enemy lines, an absolute necessity). Of course, it’s understood that such folks have been carefully screened to work in contexts which most of us would regard as somewhat risky and out of the ordinary. Equally counterintuitive, most real spies (the Cambridge Five probably being the exception), in direct opposition to the way they’re imagined in so many action thrillers, are people who leave little or no mental imprint in a crowd, their physical ordinariness being the best camouflage against detection.

From the standpoint of a writer or movie director, the admission that spies are people like us—not James Bond or Jason Bourne supermen—instantly enriches a plot’s possibilities. It pushes the plot out of the realm of puerility and pure entertainment into that of the adult, where greys predominate and three (or more) dimensions is the rule. It permits us to ask questions about courage, motivations, origins, self-doubts, the meaning of conviction, the torment of torn loyalties, the real measure of valor, and ultimately, in the struggle with conscience, growth and transformation. In the didactic novel, which The Trojan Spy certainly is, these elements trace and celebrate the arc of a character’s moral evolution, a journey which in this story leads to a truly thought-provoking denouement.

Now, perversely at a point in history when the fate of our civilization—and of the world itself—depend more than ever on truth for their survival (no hyperbole in this), the “didactic” novel has fallen out of favor. This is to be lamented because, in keeping with the toxic values that define our market-driven society, meretricious entertainment—escapism, really, and of the most irresponsible and basest sort—has inundated the public’s consciousness like a malignant fog. Some will pronounce that inescapable, considering the culture we inhabit, but this development is also rooted in a huge misconception: as the ancients knew, entertainment, truth, and didacticism are NOT mutually exclusive at all, as novels, plays, or films regarded as great art are also almost uniformly didactic. Aren’t War & Peace and The Caine Mutiny, and Madame Bovary, just to cite three very disparate works, great moral tales as well as immensely engrossing in their own right? And what about Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, or Siddhartha, by Herman Hesse? They are all unapologetically didactic, as is that extraordinarily masterful construction by William Makepeace Thackeray, Barry Lyndon. Is boring an adjective even remotely applicable to such monumental creations?

Of course, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with entertainment. Even in a world in mortal danger good entertainment plays a beneficial and possibly vital role. Ken Follett’s WWII espionage yarn, Eye of the Needle, is riveting entertainment. But here the plot refuses to rely on childish exaggerations to engage and keep the audience’s interest. Though fiction, the story rests on ascertainable truths—reality—to weave its narrative. And yes, it is a novel for adults.

The infantilization of the spy genre we witness today with its all-out negation of reality is probably the result of powerful influences originating in a degenerate film industry and the bottom-line rationale that rules so many media choices. In a clear case of the tail wagging the dog, too many specialists in the spy thriller genre have simply become adept at writing their plots with an eye to movie or TV adaptations, all of which introduces the problem of lowering the bar to fit the demands of blockbusters, the dominant vehicle in today’s Hollywood.

Such a development has no real equivalent in the past. It only fits today’s zeitgeist. Some have pointed to the pulp novel as an antecedent for this phenomenon (in its time pulp was denounced as the bastard child of high lit fiction and a threat to the “quality” short story), but the analogy is inappropriate. Whatever its defects and middlebrow horizons, pulp (which often intersected with the formidable noir genre) was often immensely entertaining and never unredeemable junk as are today’s worst actioners reveling in violence porn, because while the authors had little use for straight realism, they never totally cut the cords anchoring their plots in probable events. Pulp fiction’s muscular quality can be demonstrated by its distinguished roster of practitioners. Bounded by the pre-television years between the 1920s and 40s, and facilitated by the skyrocketing literacy rates of the working class, pulp’s exponents included H.P. Lovecraft, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett (probably the undisputed dean of the “hard-boiled” school of detective fiction), Ray Bradbury, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and even the formidable James M. Cain, who gave us such classics as Double Indemnity and The Postman Always Rings Twice. 6

Such a development has no real equivalent in the past. It only fits today’s zeitgeist. Some have pointed to the pulp novel as an antecedent for this phenomenon (in its time pulp was denounced as the bastard child of high lit fiction and a threat to the “quality” short story), but the analogy is inappropriate. Whatever its defects and middlebrow horizons, pulp (which often intersected with the formidable noir genre) was often immensely entertaining and never unredeemable junk as are today’s worst actioners reveling in violence porn, because while the authors had little use for straight realism, they never totally cut the cords anchoring their plots in probable events. Pulp fiction’s muscular quality can be demonstrated by its distinguished roster of practitioners. Bounded by the pre-television years between the 1920s and 40s, and facilitated by the skyrocketing literacy rates of the working class, pulp’s exponents included H.P. Lovecraft, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett (probably the undisputed dean of the “hard-boiled” school of detective fiction), Ray Bradbury, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and even the formidable James M. Cain, who gave us such classics as Double Indemnity and The Postman Always Rings Twice. 6

***

But whatever the monetary allure, good literature has a duty to tackle serious themes and resist the demand for mind-numbing escapism, which by now has acquired truly lethal dimensions. And the product need not be an artistic disaster, even if the perils are real. In his essay On Moral Fiction, John Gardner, obliquely (and I believe unwittingly) outlined the pitfalls confronting the artist intent on making a moral statement:

The best critical intelligence, capable of making connections the artist himself may be blind to, is a noble thing in its place; but applied to the making of art, cool intellect is likely to produce superficial work, either art which is all sensation or art which is all thought. We see this wherever we find art too obviously constructed to fit a theory, as in the music of John Cage or in the recent fiction of William Gass. The elaboration of texture for its own sake is as much an intellectual, even academic exercise as is the reduction of plot to pure argument or of fictional characters and relationships to bloodless embodiments of ideas. True art is a conduit between body and soul, between feeling unabstracted and abstraction unfelt.

Some of you may ask at this point, why this meandering peroration on the decay of the spy genre, the vanishing of the “didactic” novel, and so little about the book that concerns us here, The Trojan Spy? It’s a fair question. The short answer is that it connects us with the issue of wasted didactic opportunities, which Gaither Stewart, among other engaged intellectuals, is keen to redress, and the necessity to expose, in every venue possible, the destructive nature of the dominant world paradigm.

The spy genre—built on a staple of international intrigue—occupies an enviable position to focus its narrative on foreign affairs, and in particular United States foreign policy, by far the most influential since the end of World War II, and, of all the great powers, the most ably shrouded in hypocrisy and outright lies, with the brunt of it directed at its own population.

Loopold Trepper—the “Big Chief” of the Red Orchestra, tireless anti-Nazi, and a real life hero. If he’d been fighting for the West, he would have been the subject of a Hollywood blockbuster a long time ago.

The Second World War and the ensuing Cold War provided a great deal of splendid raw material for action thrillers with a serious message, but a lot was spent on trivializations in which the overall purpose of US foreign policy (when mentioned at all) was obfuscated or treated as untouchable and only some of its methods—as mirrored in the actions and personalities of the operatives involved—received any criticism or discussion. Nothing terribly surprising here. This is a general and firmly implanted politico-cultural approach in the United States designed to protect the legitimacy of the status quo, and fiction writers, working after all in a commercial ambit, either heed its unwritten rules or risk oblivion. Thus, for example, a good novel about the exploits of the heroic “Red Orchestra” (a sobriquet given to this espionage ring by German counterintelligence) is still to be written, as doing so would inevitably plunge the reader into a “subversive” alternate version of world history, one in which a bunch of highly resourceful and courageous Jewish communists working for the Soviet Union set out to crack the Nazis’ most sensitive secrets across Europe and succeed to an embarrassing extent.7 It is no hyperbole to say that “the Rote Kapelle” was probably the most successful spy network in WWII.7 Unfortunately, any serious exploration of such characters’ motivations leads to ideology and ideology to some kind of explanation. And this is where the tricky part begins and where most authors—fearful of having to come face to face with the larger truths informing these people’s actions, and despite the rich dramatic possibilities—abandon ship.

This “trahison des clerks”, this evasion of duty by most intellectuals (this includes the press), has collected a heavy toll not only among the millions of victims of unrestrained US power, whose truncated lives and torn bodies punctuate the path of empire, but among the American population itself, which, mired in ignorance and barraged with disinformation, has lost much of its ability to determine its own democratic future. We saw this horrid paralysis in Korea and Vietnam, and since that era in scores of other criminal interventions around the world, down to our days, when neither Iraq, nor Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, the cynical “color revolutions,” and the expanding war against Iran, and other overt and covert meddling in our name has been criticized by anyone in the commentariat and political class as downright immoral, but merely “premature”, “late”, “risky”, or “flawed in execution”. Showing their “patriotic” pragmatic chops, the establishment critics have always asked: Can we win? How do we win? They should have been asking, what on earth justifies our monstrous actions from a genuinely moral standpoint? The real left, of course, which does factor morality in its evaluations, is barely heard.

Looking at it as a triumph of self-inflicted propaganda and cultivated self-righteousness, Salvador de Madariaga, a distinguished Spanish historian and diplomat once explained the hold of a presumably noble US foreign policy on Americans:

“I only know two things about the Monroe Doctrine: one is that no American I have met knows what it is; the other is that no American I have met will consent to its being tampered with. That being so, I conclude that the Monroe Doctrine is not a doctrine but a dogma, for such are the two features by which you can tell a dogma. But when I look closer into it, I find that it is not one dogma, but two, to wit: the dogma of the infallibility of the American President and the dogma of the immaculate conception of the American foreign policy…” 8

Beyond our borders, this scandalous fraud is well comprehended. Who does US foreign policy serve, after all? The US plutocracy, of course, first and foremost, and next its associated plutocracies—fellow plunderers around the world; in sum, the global capitalist system in its latest and hopefully final incarnation. (One of its main instruments, the CIA, out of minimal decency should consider calling itself, as Alex Cockburn once suggested, the “Capitalist Intelligence Agency.” Truth in advertising, for a change.)

Against this backdrop, unmasking the main threat to global peace and survival for humanity (and the planet as we know it) is a matter of maximum urgency. Having lost with the dismantlement of the Soviet Union and with China’s turn to autocratic capitalism the old bugaboo of the “Red Menace”, the American empire is now keeping itself busy and in power via substitute threats of its own manufacture. (The “Red Menace” was largely a fabrication, too.)

The apparently open-ended “War on Terror” has paid off handsomely in this respect, and in this post 9/11 phase the ruling circles are busy tearing down whatever remains of our constitutional protections—”mission creep” some would call it—as well as rolling back the safety net and freedoms secured by workers after long decades of struggle. Thus, as the prospects for the world’s majorities recede, and the horizons darken, a virulent, warmongering global corporatism has emerged as today’s plutocracy’s outer shell and chief program.

The battle to neutralize this enormous concentration of lawless, illegitimate power won’t be easy, for, as so many observers have pointed out, even in frank decline, the American empire retains a horrendous amount of destructive capability and resources. 9

In this clime, we should be grateful for those who insist on sounding the alarm. Fact is, we need warnings, we need alerts, we need voices that can wake us up in time if we are to defeat the forces that threaten our lives while hiding behind the most elaborate body of lies the world has ever seen. The Europe Trilogy is one such warning. We should heed it and—hopefully—act on its implicit lessons.

Punto Press is proud and grateful for having been selected to carry these works to the public.

—Patrice Greanville

New York, Winter 2012

Notes

- Cairncross admitted to spying in 1951 after MI5 found papers in Guy Burgess’ flat with a handwritten note from him, but was never prosecuted. Definitely opaque by the standards of the other members, he too, may have made a powerful contribution to the anti-Nazi cause. While serving at Blechtley Park where ULTRA’s codes were cracked, Cairncross supplied the Soviets with advance intelligence about Operation Citadel, and in particular the Battle of Kursk, the world’s largest tank battle, which sealed the fate of the Wehrmacht in the East. Why did the allies prevaricate on this information so vital to turn the Nazi tide in the East and it took a spy to confirm it? This raises interesting questions about the allies’ true level of loyalty to the Soviets.

- Ann Talbot, Le Carré’s new novel questions his previous Cold War certainties (http://wsws.org/articles/2001/feb2001/book-f15.shtml 15 February 2001)

- The Cambridge Spies, Phillip Knightley, BBC History (http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/coldwar/cambridge_spies_01.shtml 17 February 2011)

- Excerpt from the revised foreword by the author for this edition.

- Peter Howell, Mission Impossible 4 vs. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (http://wsws.org/articles/2001/feb2001/book-f15.shtml 15 December 2011)

- “The low price of the pulp magazine, coupled with the skyrocketing literacy rates, all contributed to the success of the medium. Pulps allowed its readers to experience people, places, and action they normally would not have access to. Bigger-than-life heroes, pretty girls, exotic places, strange and mysterious villains all stalked the pages of the many issues available to the general public on the magazine stands. And without television widely available, much of the free time of the working literate class was spent pouring through the pages of the pulps.” (Excerpted from What is pulp fiction? The Vintage Library. (http://www.vintagelibrary.com/pulpfiction/introduction/What-Is-Pulp-Fiction.php))

- The Red Orchestra (German: Die Rote Kapelle) was the name given by the Gestapo to an anti-Nazi resistance movement in Berlin, as well as to Soviet espionage rings operating in German-occupied Europe and Switzerland during World War II. The term ‘Red Orchestra’ was coined by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA), which referred to resistance radio operators as ‘pianists’, their transmitters as ‘pianos’, and their supervisors as ‘conductors’. “Red” stood for communism. Thus, German counterintelligence called the Soviet covert network die rote Kapelle (“the Red Orchestra”).

- Quoted by John Gerassi in Violence, Revolution, and Structural Change in Latin America (Random House, 1969).

- The US is a wounded colossus alright, wounds self-inflicted at that, and perhaps the first great civilization on its way to be done in by its own lies. Some day perhaps some wit will say that propaganda killed the beast, although this is a beast that far from being a victim was largely a victimizer, till the bitter end.

But wounded as it may be, this colossus still commands an awesome amount of lethality, and a dizzying array of resources to cast a long, ominous shadow across the world … dwarfing those found anywhere else. The magnitudes are staggering, and most of the world is quite aware of them. America’s military—charged with policing the world—still outstrips the military muscle of all other nations combined, and no real retrenchment to true defensive missions is foreseen on any front.

The US has more school buses in just one county of New York state than exist in all of Argentina; more actors than the whole population of Berlin in the Napoleonic era; it has more warplanes than all other air forces combined (just its private cargo fleet, operated by Fed Ex, UPS, etc., surpasses the air forces of numerous countries, including Canada, Spain, Belgium, Chile, Egypt, etc.). The size of its economy—though now slowly ceding ground to rising powers—is legendary. New York City’s budget alone matches Israel’s, and California, New York, Texas, and Connecticut—if they were independent republics—would outstrip all nations except the top five in financial, scientific and military power. Similar lopsided statistics can be found in many other fields.

ADDENDUM:

The American media’s take on spies.

I have just published a review of Mr. Stewart’s phenomenal book in amazon.com! As I have told my friends, and mentioned in my review, it is doubtless the best book I’ve read in a decade. I truly hope that this classic is showered with literary awards it so richly deserves and, more importantly, is a conduit to educate our democracy about the very real dangers parading as hyper patriotism, security and false allegiance to covert philosophies and machinations that are siren calls destruction of what we all hold dear.

I have to concur with Ms. Pishney.

I think this book’s topic—a complex one— is masterfully developed. Mr Stewart truly deserves what others have called him, a new John le Carré, albeit in his case, since he has been writing novels and essays for a long time, a yet-to-be-discovered great writer.

As the prior reviewer says, it is and deserves to be called a classic.

T.E. Landsowne,

Bristol